Mick Clifford: Past meets present for a life lost and legend born

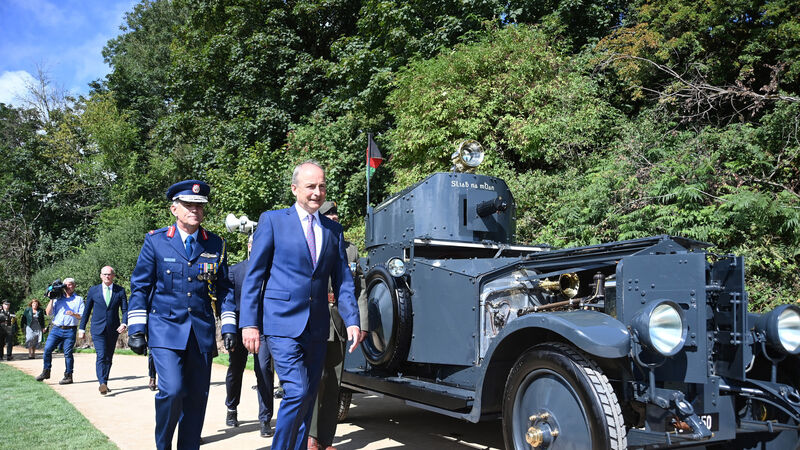

History caught up with the present at Béal na Bláth.

The division, sowed by a brutal Civil War a century ago, was symbolically closed with the joint orations of Micheál Martin and Leo Varadkar at the place where that conflict’s most fabled casualty, Michael Collins, met his end.