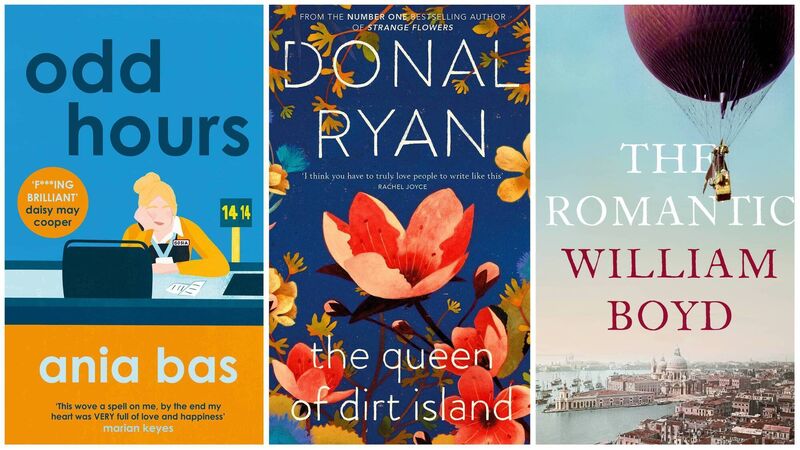

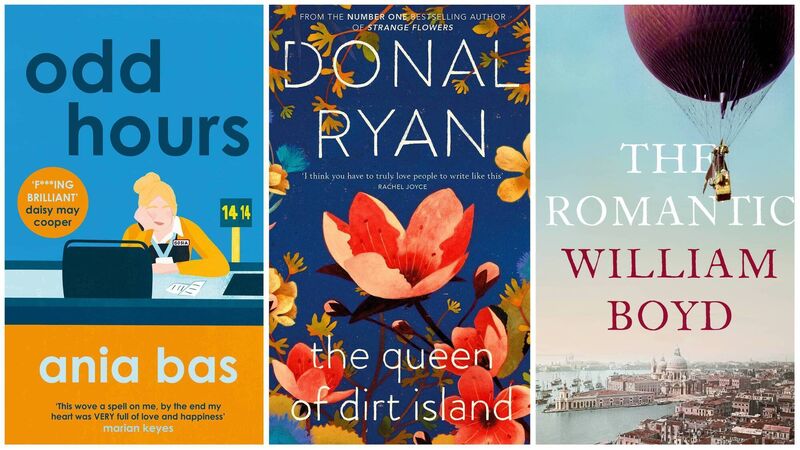

Books of 2022: Classic characters at the heart of the year’s best books

Kevin O’Sullivan's novel of the year is Ania Bas’ Odd Hours

My novel of the year by some distance has to be Ania Bas’ Odd Hours (Welbeck).

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Kevin O’Sullivan's novel of the year is Ania Bas’ Odd Hours

My novel of the year by some distance has to be Ania Bas’ Odd Hours (Welbeck).

This enigmatic and idiosyncratic gem is eccentric, quirky and utterly original. The protagonist Gosia is one of the most memorable and most beautifully realised characters I can remember. She is bizarre but believable, hugely flawed but still somehow memorable and even inspiring.

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.

© Examiner Echo Group Limited