Daniel McConnell: Is Sinn Féin ready to go from a party of booing to one of doing?

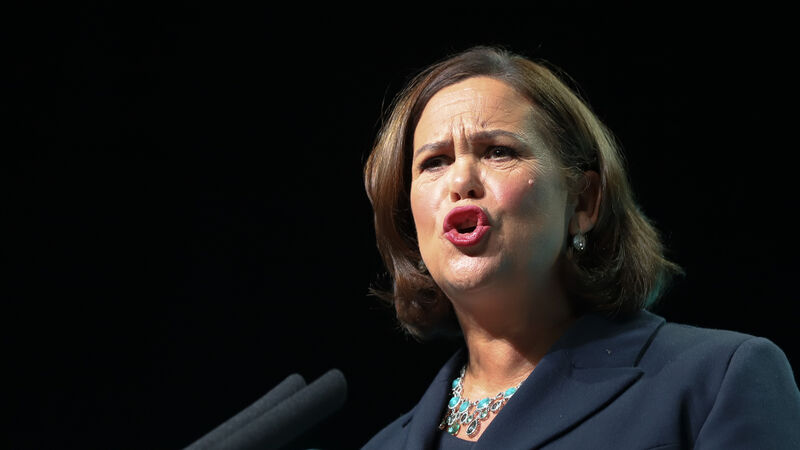

For all of her party’s inconsistencies and policy limitations, Mary Lou McDonald is now seen as potentially Ireland’s first-ever female Taoiseach

Anyone who knows politics understands that being in government is a world away from what life is like as an opposition party.

In opposition you speak, in government you act. Going from a party of booing to one of doing is rarely an easy transition. But the prize is substantial if it can be achieved.