Jackie Tyrrell, the man who had everything, retires

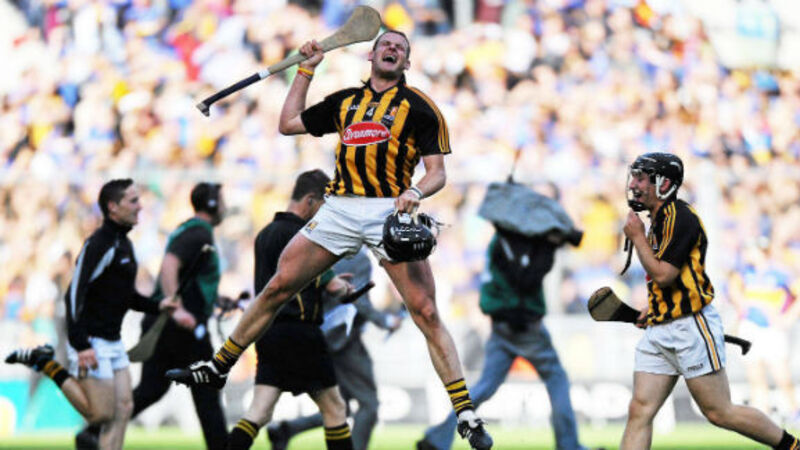

This celebrated image is taken immediately after that final whistle, bareheaded, helmet in left hand, hurl in right hand a gauntlet at the sky. His frame hangs above Croke Park in a photograph’s eternity, Tipperary the favourites beaten and Lar Corbett remorselessly squeezed and Jackie Tyrrell, son of The Village, gone to a dream of flight.

Kilkenny had done it, against the odds. He had done it while marking Corbett, incumbent Hurler of the Year.

That victory became a doubled moment, protecting achievements of the past decade, initiating advances in the coming decade. 2011 ended up anvil pressure, a forge choked with heat. Now Kilkenny were masters of their soul, free in open air. Hurlers always, they had proved themselves best of men.

Jackie Tyrrell became central to that pivotal season and not least when Dublin took spring’s NHL Final by 12 points. Tyrrell did not stint himself or colleagues, admitting a couple of days later: “It was the worst performance I was ever involved in with Kilkenny.” The rally began there, with the kind of frankness only genuine authority can deploy.

This retirement breaks another link with the team of 2006, which set in train eight Senior titles in ten seasons. Only Eoin Larkin, close friend and clubmate, is left of those 15 starters. Then 24, Tyrrell captained Kilkenny to that September glory, same as he had helmed the county’s U21s three years earlier.

The phenomenal haul of silverware, centred on nine Celtic Crosses and four All Stars, includes captaining James Stephens to Senior success (2011) and Leinster to Railway Cup success (2012). There were two Fitzgibbon Cups with LIT (2005 and 2007). Only a Minor All Ireland escaped his clutch.

Some of Jackie Tyrrell’s intriguing qualities remain unremarked. Same as Martin Comerford, he challenged Kilkenny hurling’s sense of itself, the delusion that best exponents are all knacky stylists. Tyrrell was not earmarked as a Senior prospect, someone who would rise near the sun. Part of his tremendous legacy for young hurlers is the kinetic nature of sheer desire.

Franny Cantwell kept goal for James Stephens during the 1990s and 2000s, standing between the posts when the club won 2005’s Senior All Ireland. “I saw Jackie from the start,” Cantwell states. “Some doubted but I remember saying to fellas in work that we had this young lad who’d go to the very top of the game. You could just see the right stuff in him.”

Cantwell continues: “I’d describe Jackie Tyrrell as the man who had everything, the man who gave everything, and the man who won everything. Jackie is a born winner. He should go on in time to be an excellent selector and manager. But we want a few more seasons from him with The Village, first.”

Cantwell finishes with a caveat: “I don’t think he ever got the credit in the media for how good he is hurling wise. It was all about his physique, his toughness… There is far more to Jackie than his strength.”

If nobody ever doubted Jackie Tyrrell as a warrior, his technical skill somehow got ignored. Here is an orthodox righthander taking sideline cuts off his left side and frees off his right side. How many peers had Tyrrell in this regard? Small few, save Galway’s Ollie Canning. Of current players, Tipperary’s Jason Forde and Wexford’s Conor McDonald are similarly ambidextrous. The finesse associated with those last three names speaks for itself.

Remember as well how Tyrrell’s remarkable length of drive off his left side provided tactical boon. As teams started, in the mid 2000s, to crowd the middle third when defending puckouts, funnelling out forwards as extra midfielders, Tyrrell would be slipped the odd short puckout by James McGarry. Next moment, the ball landed below in the opposition’s full back line. Next moment again, those forwards were being funnelled back in.

All the while, Jackie Tee stayed himself. He is one of the game’s singular personalities. An out and out dandy, he makes like Kerry’s Paul Galvin. We should enjoy the lovely irony of such pristine clotheshorses being generation best at winning dirty ball. There is something of the Argentinian polo player about Jackie Tyrrell, a relaxed but honed machismo. Same as with Galvin, Tyrrell’s ebullience and self confidence rubs up some people the sharp way, as the truly self-confident often do. If you meet Jackie Tyrrell, he comes across as a veteran of his own mind, someone who stared down worst fears and doubts.

I often thought he was like a man who had survived gunfire. Maybe it is not Argentina but frontier America that offers analogy, the gunfighter so skilled and so canny that he survives to retire.

Every squad, to retrieve a big setback, needs iron believers. Back in 2011, Kilkenny were underwhelming winners over Waterford in an All-Ireland semi-final. Meanwhile Tipperary were mowing ground, seven goals slotted in the Munster Final against the same Waterford. The county of Kilkenny was a concertina of anxiety about what might transpire in this All-Ireland Final.

I was none too certain myself until a friend who has a city centre pub passed on a story. The Monday after that semi-final win, Jackie Tyrrell appeared in the door with Eoin Larkin and a couple of other Kilkenny hurlers. They were in right form, high wattage good humour, off on a bit of a skite before battening down the heads for Tipp.

The hurlers got drinks, got settled. This pub is a boozer, an echo chamber. “Bet all ye have on Kilkenny against Tipp,” Tyrrell said to nobody in particular and everybody to hand. “Bet the whole house. Tommy Walsh is pure fit to be tied. He is just lowing to get at Tipp…” As so often, Jackie Tyrrell’s judgement proved sound. His words, even in that blur, flew, being a guarantee.