Kieran Shannon: What happens when two finalists go back to war?

Brian Sheehan, Kerry, tussles with Ryan McMenamin, Tyrone in Omagh in February 2009. Pic: Oliver McVeigh / SPORTSFILE

With him being around as long as he has at this point, there are certain things Jack O’Connor has come to experience and appreciate as much as anyone, like just how spiky and relevant a league encounter between the previous year’s All-Ireland finalists can be.

Twenty years ago to help with the process of writing his book , O’Connor kept a diary. The last entry before a game in Omagh was by his own admission “full of vim and vigour”.

“We’re heading up north to play it honest and hard,” he’d log. “This game is exactly what we need. Let’s try our case. No hiding.”

The previous September he felt some of his players had shirked matters. In the opening minutes of that 2005 All-Ireland final the finger of a Tyrone player ended up in Colm Cooper’s eye. “If a couple of our players had gone in and got a hold of the culprit, the referee would have been forced to do something,” O’Connor would write and learn.

“I tell the lads [now] again and again, we have to be paranoid. The bastards ARE out to do us.” In the first subsequent rematch of the sides, Kerry duly played like the hunters. At halftime they were four points up having played into the breeze. “Our workrate was excellent.” In the second half they were reeled in. “The crowd in Omagh was very hostile and they pressurised the officials into marginal decisions,” O’Connor contended. Tyrone squeezed out a win by two points but O’Connor took solace. “We learned a lot.” The second half emphasised the need to counter-attack at greater pace and minimise soloing into tackles. While Kerry had lost that battle they took enough from it to win that year’s war: at the end of that campaign their booty included Sam Maguire and the league title.

Three years later he headed back to Omagh in even more vengeful mood. He had just been again entrusted with the keys to the kingdom and a side coming off yet another defeat and tutorial from Tyrone in Croke Park.

“There [was] an edgy feel about Kerry all day,” Mickey Harte would write in a book he brought out himself at the end of that 2009 season. “Over the years any conversation I had with Jack O’Connor were confined to a few chats on the odd All-Star trip or sharing a table at the All-Stars banquet. Jack wasn’t passing the salt on Sunday. Before the game I strolled down the line to shake his hand as the ball was being thrown in. Jack shook my hand but was already locked in watching the game. Although it [was] only a league match, Kerry [were] here to leave a dent on us.”

By halftime Tyrone were shipping serious water, trailing 2-8 to 0-3. Harte scanned his dressing room and intuitively decided that while a result was beyond his team, pride was salvageable. For years he had preached to his teams, usually from a winning position, that the second half was a new game. That afternoon in Omagh he took that concept to an extreme, asking kit man Mickey Monagh if he had a second set of jerseys.

“We needed to start fresh. I called each player up and handed him his [new] jersey. The players put them on unison. A new beginning.” In a second half that featured scuffles between Ryan McMenamin and Paul Galvin and some that even ensnared Marc Ó Sé and O’Connor himself, Tyrone held Kerry to just two points to lose by only three. “That was massive for us,” Harte would write. There had been something for everyone. When later that year Kerry won the league and then Tyrone won Ulster and then Kerry won the All-Ireland, each party could point to the spirit shown in that battle in Omagh.

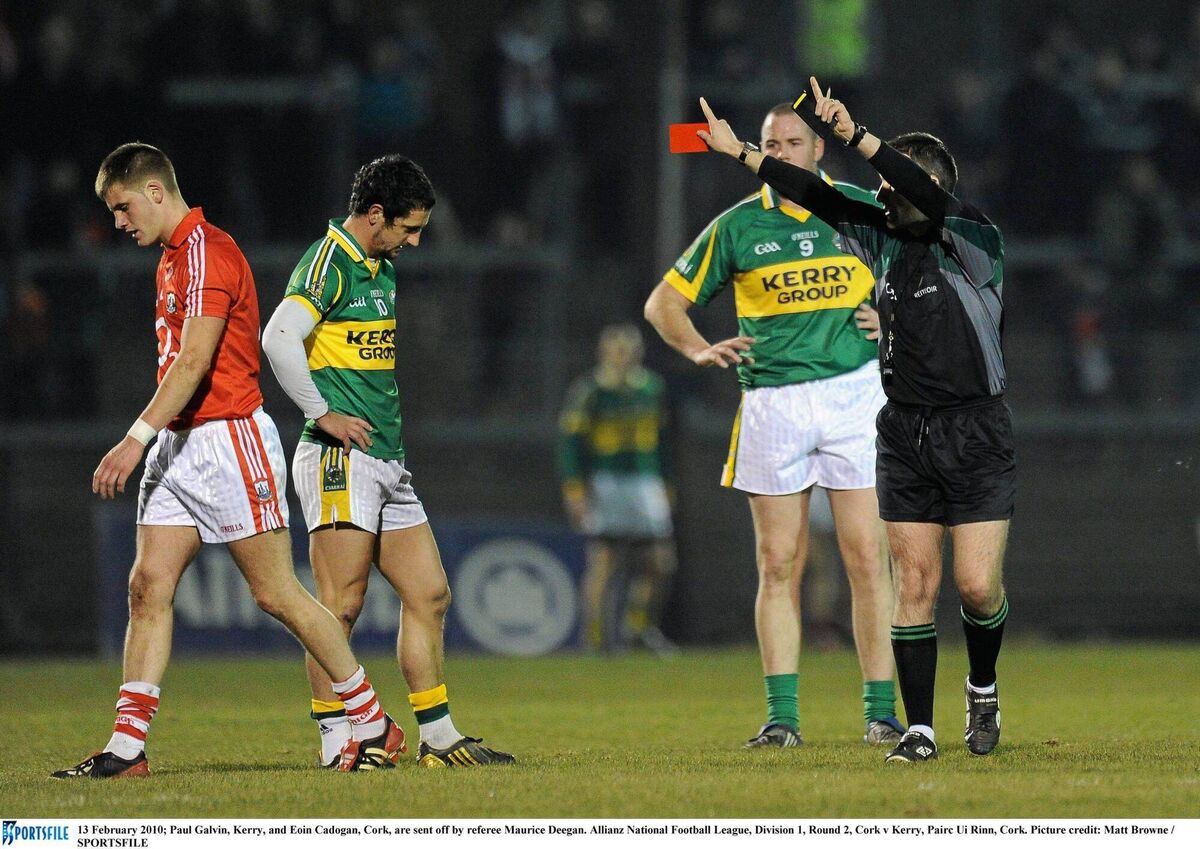

That was very much the mood music in those days. Twelve months on from his entanglement with McMenamin up in Omagh, Galvin found himself wrestling with Eoin Cadogan in Páirc Uí Rinn, something he believed Cork intentionally initiated, smarting from the previous September and Tadhg Kennelly’s outrageous hit on Nicholas Murphy.

Again that league game was tempestuous, again the previous year’s All-Ireland runners-up emerged the winners, and again the champions had little to be perturbed about; Kerry later that year beat Cork in Munster, with Galvin at the peak of his powers. But upon a further flashpoint with Cadogan in Páirc Uí Chaoimh, Galvin’s suspension opened the way for Cork to win their All-Ireland, fuelled by that year’s league title, which itself may not have happened only for a win against Kerry that February.

Once Jim Gavin came along though, he completed bucked the dynamic between All-Ireland finalists playing each other in the following year’s league.

In the decade prior to him winning All-Irelands, six of the nine league encounters between the previous year’s All-Ireland finalists were won by the team who had been left empty-handed in Croke Park.

In 2014 as Gavin’s team went about trying to retain their national league and All-Ireland titles, they were pitted against Mayo in round six. The previous three seasons at that precise juncture Mayo had defeated the reigning All-Ireland champions: Cork in 2011, Dublin in 2012, Donegal in 2013. And in each of those years James Horan’s men had beaten those teams again in championship. Defeating the team that had edged them in the 2013 All-Ireland final could mark the most significant signpost and scalp of them all.

Mayo played some scintillating football that Saturday night under the Croke Park floodlights. By halftime they were three points as well as a man up, Stephen Cluxton having kicked out at Kevin McLoughlin as another kickout of his was delayed or disrupted.

Yet Dublin wouldn’t bend. Two late Eoghan O’Gara goals earned the 14 men a draw. For Mayo it felt like a loss. They wouldn’t beat Dublin in league or championship for the rest of the decade, albeit they would fail much better on the biggest stage of all. It was as if they’d calculated all pre-August wars against Dublin as phony – while Dublin decided they weren’t going to lose to anyone at any time. It was nothing personal against Mayo; in 2016 Kerry were similarly kept in their place in both the opening and final game of that year’s league.

“When I think of all the league games we had over the years, the one that stands out is beating Kerry in Killarney in 2010,” says Paul Flynn. “When you’re in the chasing pack, you can get an awful lot of momentum and belief from beating the All-Ireland champions in the league.

“I actually don’t remember much about all the leagues we won. Under Jim we became almost emotionless. It didn’t matter who were playing, whether it was a Roscommon who could have been bottom of the league or a Kerry or Mayo that we had beaten in the All-Ireland final. We treated every game the same. And that might have worked in our favour. The other team might have been all riled up to get one back over us while we were just emotionless and ruthless.

“But we definitely traded off keeping people down. We would never let anyone up for oxygen if we could.” Eventually they had to relent. In 2019 they failed for the first time to reach a league final under Gavin, losing to a Tyrone team they had beaten in the previous year’s All-Ireland final.

It didn’t sit well with them. In the dressing room afterwards Galvin ordered his players to absorb the silence and hurt: Someone else the following week was going to be going up those steps and taking “our cup”. Their response was a bout of animal training to ensure they retained Sam Maguire. Even after Gavin departed, Dessie Farrell ensured that any side Dublin had beaten in an All-Ireland final were reminded of the relationship’s hierarchy, including Kerry in early 2024 when they were trounced 3-18 to 1-14.

Jack O’Connor was stung after that, and informed by it; in 2025 he’d target winning a league, knowing it invariably leads to a championship. It’s a trend Éamonn Fitzmaurice for one believes he’s out to extend this year as he bids to go back-to-back for the first time in his career. But his motivation for Ballyshannon this weekend can hardly match that of his opposite number.

“This weekend is not a big game for Kerry,” reckons Flynn. “If they were at home it might be different but they’re not. But it is a huge game for Donegal.

“I was at their game against Dublin and you could see in the first half they didn’t deploy a zonal system; they played a certain man-to-man system that still allowed for great double-ups and triple-ups. That is the thing about the league; you’ll try out certain things for a stretch of a game, just never for a full game. McGuinness has obviously worked on something.” Darran O’Sullivan who soldiered with O’Connor for many league campaigns is of a similar mind. “McGuinness will go for the win. Not to lay down a marker or right the wrongs of the final last year but to show his players that they’re right there with Kerry.

“A bit of me is thinking Jack should nearly leave David Clifford at home and give him the weekend off, but it’s still a good game for Kerry. Jack will look at it as a great test of character of certain lads he’ll want to have a look at. He’ll want a performance more so than points, but also feel if he gets a performance he could get the points.” Unlike Omagh 20 years ago, O’Connor might be now be more the hunted than the hunter. But still he’s heading up north, looking to play it honest and hard. Try his case. No hiding.