Is the new vacant homes tax designed to fail?

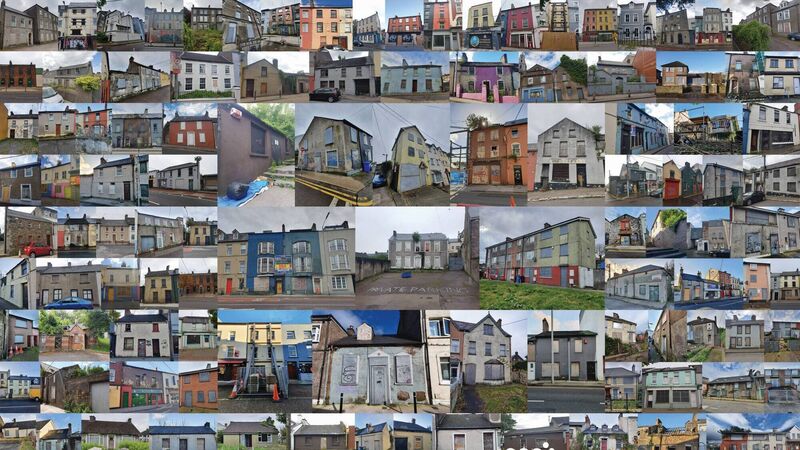

Derelict properties are already exempt from the Local Property Tax and will also be exempt from the Vacant Homes Tax. File photo: Frank O'Connor and Jude Sherry, Anois

When it comes to housing in our Republic there’s no doubt that these are extremely stressful times for many, with estimates of 10,500 homeless and 290,000 classified as hidden homeless.

Yet we have 255,000 under-used houses that are either vacant, derelict, or holiday homes. After years of toing and froing, the Irish Government has finally decided to discourage under-use and vacancy through a Vacant Home Tax (VHT).