Clodagh Finn: A timely reminder – the road to repeal was paved with heartache for Irish women

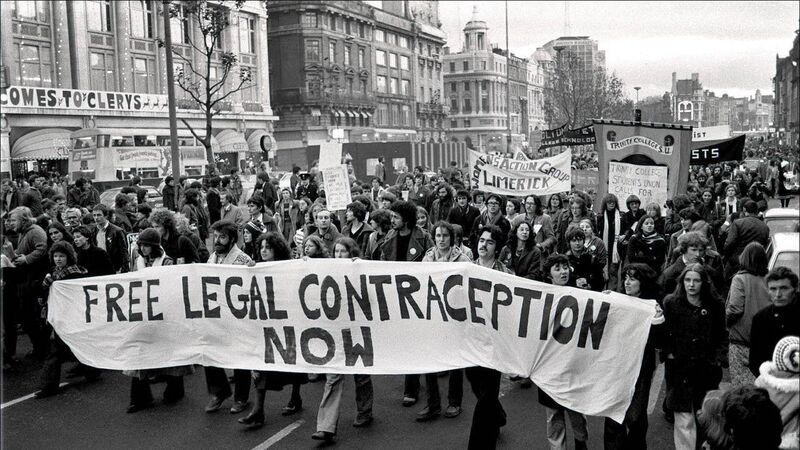

The sale of contraceptives was illegal in December 1978 when the Contraception Action Programme called for the provision of free legal contraceptives. Nearly 44 years on, what they demanded is, partly, being provided. Picture: Derek Speirs

What resonant timing: On the very same day that free contraceptives for young women aged between 17 and 25 are due to become available at GP surgeries, a new book charting the torturous and tortuous 50-year battle to get to this point will be launched.

(Lilliput Press) will get its ceremonial lift-off in the Mansion House in Dublin tonight.