Clodagh Finn: Are we about to see a new golden age for trade unions?

Earlier this year, Mick Lynch, the eloquent, popular general secretary of the union (RMT) that led one of the biggest rail strikes in the UK in recent decades, named the Irish labour leader and revolutionary James Connolly as his hero.

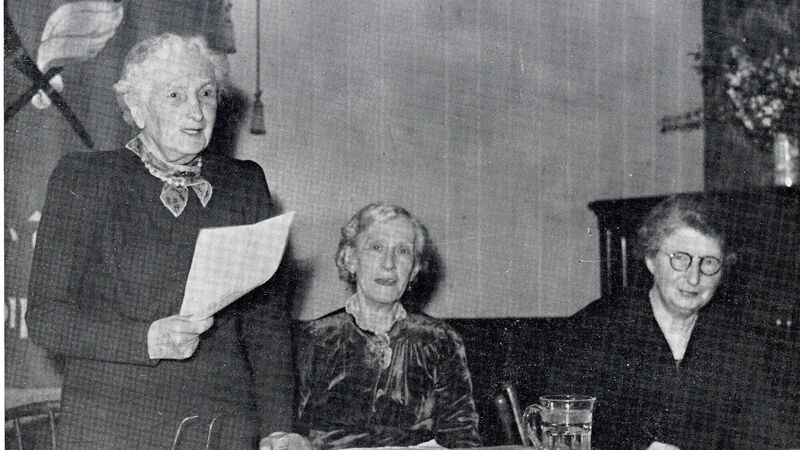

This week, I was reminded why trade union leader Louisa ‘Louie’ Bennett was one of mine. I’m sure she made many rousing speeches in her time, but it was something she said at the end of her life that resonated with me the most. Indeed, it will speak to anyone who suffers from impostor syndrome (which is most of us, if we’re honest, or if we have any self-awareness at all).