Sean Murray: Stardust inquest to get underway

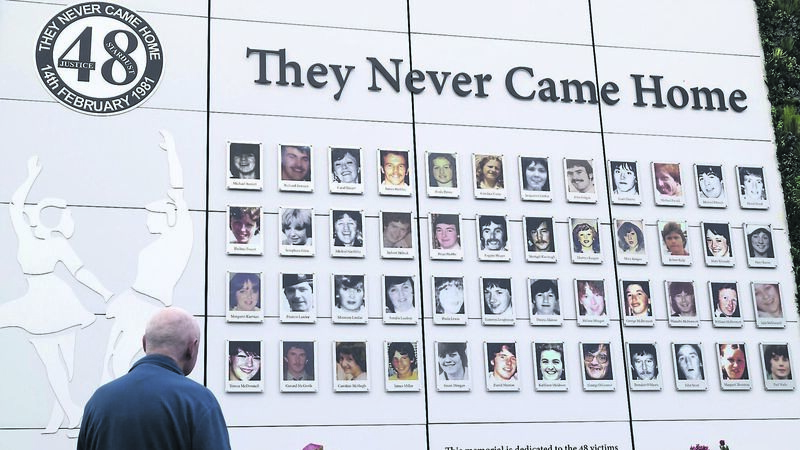

The memorial to the 48 victims at the site of the Stardustnightclub in Artane. The victims perished after a fire broke out at a St Valentine’s disco-dancing competition in 1981. Picture: Colin Keegan/Collins Dublin

As 2019 came to a close, “finally next year could be the year for the Stardust families” might have felt an accurate prospect.

In September that year, the Attorney General had granted new inquests into the deaths of 48 people in the Stardust nightclub in North Dublin in 1981. Most of them were teenagers or in their early 20s when they perished in the blaze.