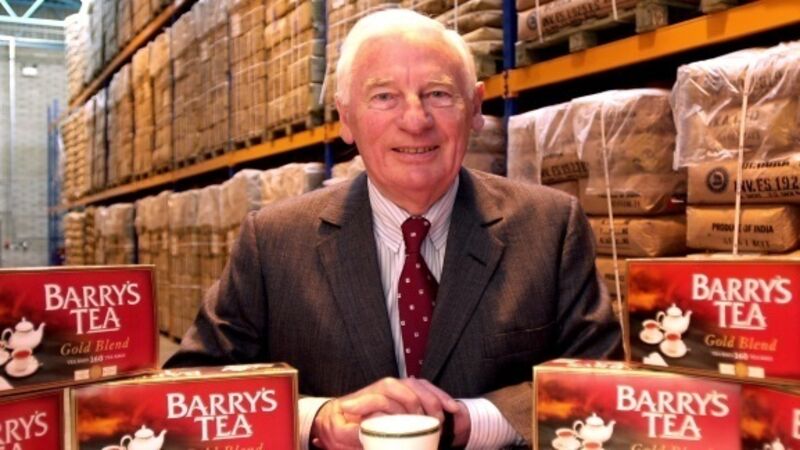

Peter Barry: A key architect of peace and king amongst Cork’s merchant princes

PETER Barry never led his country or his party but he was in the vanguard of the politicians who brought peace to the island of Ireland.

He was the true blue Fine Gaeler who harboured instincts on the national question that were usually the preserve of Fianna Fáil. Among Cork’s merchant princes, he was king, yet he wore his success in business and inherited wealth lightly, always more conscious of his obligations than entitlement. For many who encountered him though, he was just a decent man who did his best to make a difference, using the competence, charm, and not a little steel when required.