Dublin and Cork rising sea levels show scale of global challenge

Urgent action needed: Ireland’s marine territory of approximately 500,000 km2 is some of the most biologically sensitive and important sea areas in EU waters

The recent Irish Ocean Climate and Ecosystem Status Report 2023, published by the Marine Institute, is an important report highlighting a number of factors impacting on Ireland’s marine environment and ecosystem as the planet’s temperatures continue to rise.

The report represents a collaboration between marine researchers within the Marine Institute, and includes authors from Met Éireann, Maynooth University, the universities of Galway, Trinity College, the Atlantic Technological University, National Parks and Wildlife, Birdwatch Ireland, Inland Fisheries Ireland, The National Water Forum, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Dundalk Institute of Technology.

Ireland’s climate is dominated by the influence of the Atlantic Ocean. The ocean and the atmosphere are a tightly coupled system with heat and mass continuously exchanged between the two.

Atmospheric circulation affects ocean circulation, with surface winds generating ocean waves and currents. The transfer of heat and moisture from the ocean to the atmosphere influences weather and climate patterns globally.

Michael Gillooly, Director of Ocean Climate and Information Services (OCIS) at the Marine Institute, emphasised the importance of the oceans on Ireland as an island nation on the western edge of Europe and noted that “among the key findings of the report are sea level rises of between 2-3mm per annum since the 1990s; a rise of approx 0.5 degrees in sea surface temperatures on Ireland’s north coast over the past 10 years; increased acidification of surface waters and year-round presence of harmful algal species — probably due mostly to increased temperatures caused by human-induced climate change”.

“We’ve seen about 40cm of sea level rises since the 1850s, and we think that the continued rate of rise is going to be somewhere between 3 and 10 mm per year, depending on what part of the Irish coast you’re looking at,” explains Glenn Nolan, Section Manager, Oceanographic and Climate Services, Marine Institute.

“The other factor in this is the impact of that warming ocean upon the things that live within it — shellfish and commercial fish species as prime examples — and where the effect is going to be felt. We have already seen evidence of warmer water species, which would not have been very common in Irish waters up to a few years ago, become more dominant over recent years.

“Disentangling the effects of long-term fishing from the impacts of climate is challenging. We have seen some evidence of warm water fish like anchovy increasing in our waters in recent years, but whether this is due to climate change impacts is the subject of ongoing research.”

Ireland’s marine territory of approximately 500,000 km2 is some of the most biologically sensitive and important sea areas in EU waters and includes major spawning grounds of Atlantic mackerel, horse mackerel, blue whiting, hake and cod.

This sea area supports a marine economy of over €5 billion annually, employing over 70,000 people directly and indirectly, particularly across coastal communities.

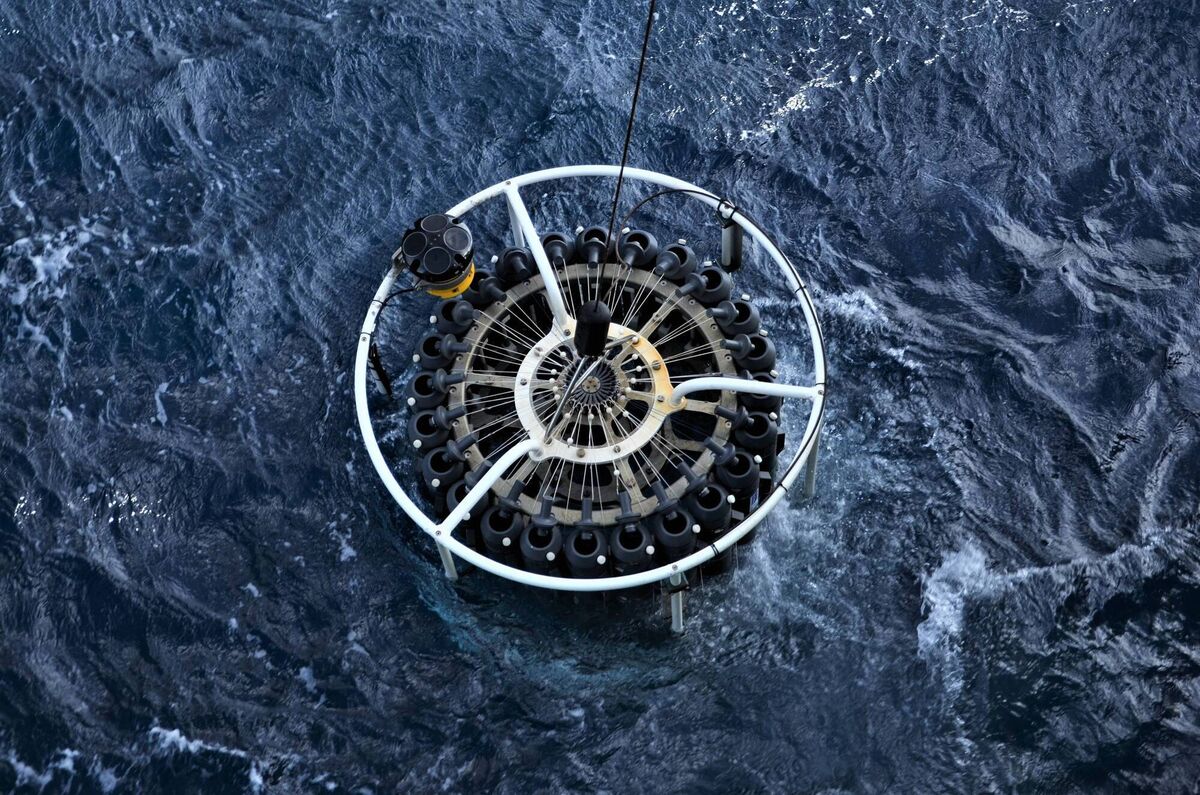

Glenn leads the oceanographic and climate services team, where the oceanographic data generated by the Marine Institute and other data providers is harnessed to build a picture of how the ocean around Ireland works and how it is changing over time.

“We make these products and services available to scientists within the Marine Institute and deliver them to other public sector bodies, universities and the private sector,” Glenn said.

The typical sectors supported include research, fisheries, aquaculture, environmental monitoring, ocean energy, search and rescue, shipping and tourism and leisure.

“Our colleagues in the Geological Survey of Ireland do a lot of work on what is called ‘coastal vulnerability’ — assessing the entire coastline of Ireland to determine which are the most vulnerable areas and how rising sea levels are going to affect them. Obviously, those hard shore areas with cliffs and rocky shores will be less impacted than soft shores areas such as beaches where more erosion will occur.

“We work with colleagues in the Geological Survey to try to map out what some of those changes look like over time, bringing in factors like changes in wave climate and sea level in the makeup of the shore itself to get an idea of what places might experience the worst effects of sea level rises and coastal erosion. Obviously, over time it does have the potential to effect coastal communities or any urban centres that are near the shore.”

While many parts of the world have experienced the often dramatic effects of rising temperatures due to climate change, Ireland may well experience cooling as a result of the ongoing lessening of the Gulf Stream, which gives the country its temperate climate.

The Gulf Stream ocean current, bringing warm water from the Gulf of Mexico into the Atlantic Ocean, is predicted to decrease by 30% into the future, with a low risk it could collapse completely. Also known as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, there is evidence of its weakening, with Irish surface waters cooling in recent years after peaking in 2007.

“The Gulf Stream has an effect in terms of moderating our climate, originating in the sub-tropics off the Florida coast and the Gulf of Mexico,” Glenn explains. “Given its moderating effect on the European climate, so any slowdown in it could have implications for the weather and climate of Europe as well. If there is less heat in that current and it is a little less robust, it would carry implications for the European continent.”

- The ocean and the atmosphere are a tightly coupled system. Atmospheric circulation affects oceanic circulation with surface winds generating ocean waves and currents.

- Sea levels continue to rise around Ireland. Larger local sea level rise has been observed in Cork and Dublin, with recent rates of relative sea level rise being twice the global average in Dublin.

- Gulf Stream System is key to Ireland’s mild climate but is predicted to decline due to climate change.

- The North Atlantic Ocean is one of the most intense ocean sinks for atmospheric CO2 in the Northern Hemisphere.

- Irish offshore surface waters have become more acidic with an overall reduction in pH of 0.02 units per decade.

- Impacts of climate change on the seafood sector from harmful algal bloom events are expected to occur more frequently.

- Disentangling long-term fishing effects from the impacts of climate change is difficult. Climate change cannot be examined in isolation of these effects.

- Warming waters may allow for new fishing opportunities (e.g. boarfish and anchovy), but it is imperative that new opportunities are managed effectively and sustainably.

- Approximately half of seabird species globally have declining population trends.

- 89% of seabirds impacted by climate change are also affected by other threats such as overfishing, incidental capture, hunting/trapping and disturbance.