Mick Clifford: Call for day to commemorate Anglo-Irish Treaty and reconcile people across island

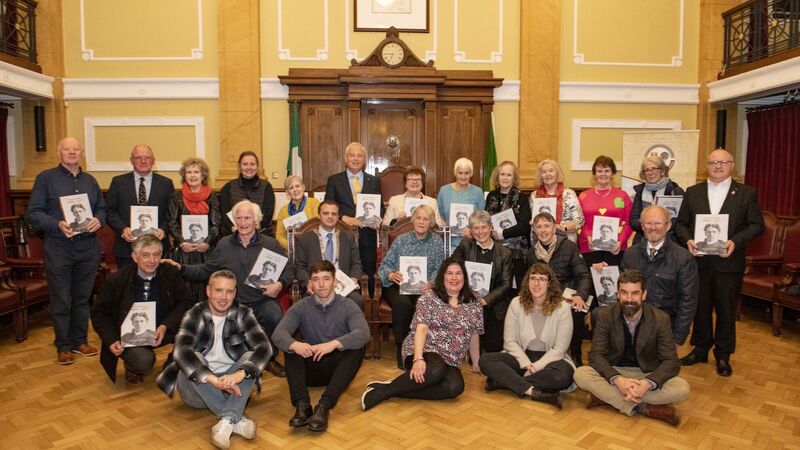

Some of the grandchildren and greatgrandchildren of Diarmaid Fawsitt who were present at the launch of their grandfather's archive. Included is Cllr. Shane O'Callaghan who deputised for the Lord Mayor of Cork; Brian McGee, Senior Archivist, Cork City and County Archives Service; Gabriel Doherty of UCC and former Lord Mayor, Cllr. John Sheehan. File picture: Brian Lougheed

Diarmuid Fawsitt was called home from the US to help out with the Treaty negotiations of 1921. He was one of 11 children born in Ballymacthomas, Co Cork, to a Protestant father and Catholic mother. He was raised by his mother’s family and attended the North Mon where he got to know Terence MacSwiney and Tomás McCurtain.

DeValera sent him to the US in the Autumn of 1919 to represent the new government and negotiate the treacherous straits of Irish-American politics. He didn’t take part in the Civil War but was pro-treaty.