'Don’t get hung up on decriminalisation': Citizens’ Assembly set for drugs laws vote

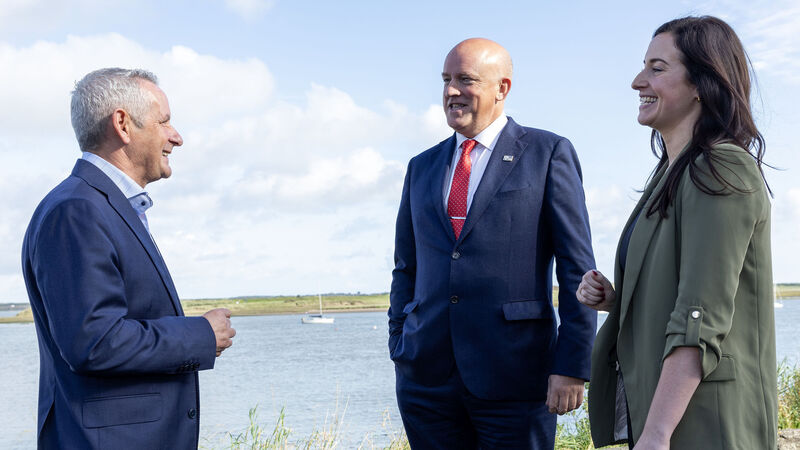

(Left to right) Paul Reid, Chair of the Citizens’ Assembly, Aubrey McCarthy, Co-founder and Chair of Tiglin Rehabilitation Centre and Laura Dunleavy, Kinship Care Ireland, at the Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use earlier this month. Picture: Maxwells

There was a moment during a meeting of the Citizens’ Assembly on Drugs Use in early September where a member stood up and expressed frustration over what decriminalisation of drugs actually meant.

The member said they had been circulated a document compiled by the assembly secretariat which said that under decriminalisation, drug possession would no longer be a criminal offence, but that it would still not be legal.