Clodagh Finn: Recalling the Irish suffragette who was one of Gandhi’s trusted allies

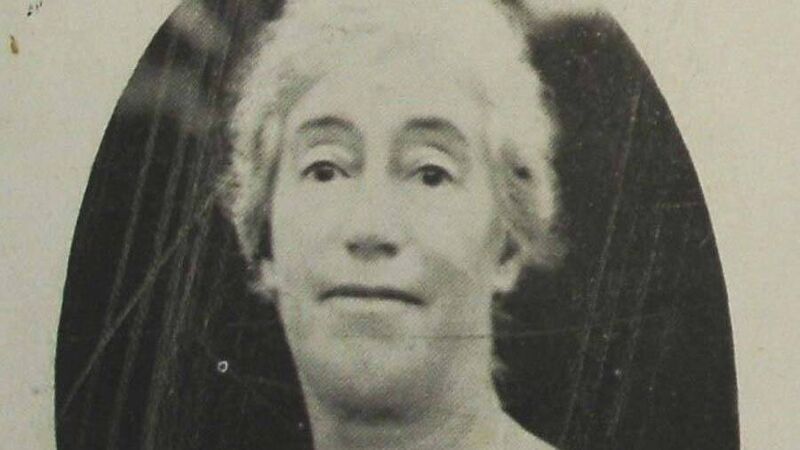

Margaret Cousins knew Gandhi and recalled sitting on the floor of his cottage early one afternoon discussing “education from all angles”.

In all of the coverage of the seismic events that took place in Ireland 100 years ago, one rather overlooked story made me sit to attention.

We heard a whisper of it during Treaty Live, RTE’s playful and thought-provoking special that rolled back a century of history, as if on casters, to bring us ‘live’ into the heart of the signing of the Anglo-Irish treaty. The ‘news’ that piqued my interest came in a dispatch from Associate Professor of History, Jyoti Atwal, who was beaming in live from the India of 1922.