Fergus Finlay: To blink, to ink: I feel for Collins and the pressure he was under in 1921

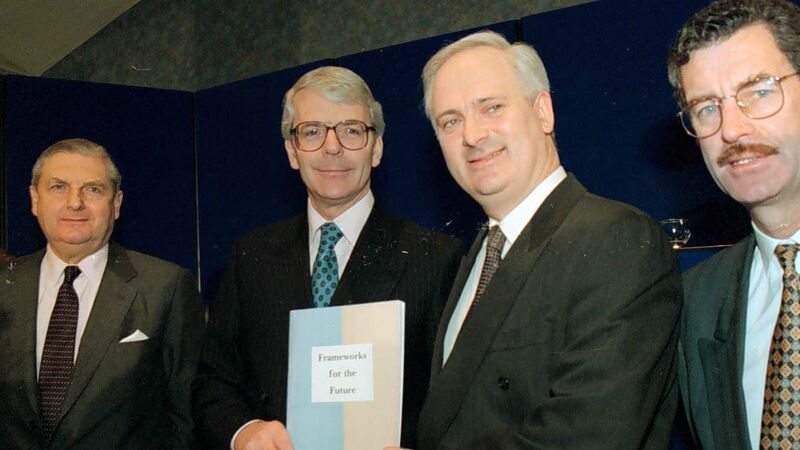

Patrick Mayhew, John Major, John Bruton and Dick Spring with a Framework for the Future of Northern Ireland that was fundamental to laying the groundwork for the Good Friday Agreement.