Clodagh Finn: Time to bring the brilliant sisters of famous men into the limelight

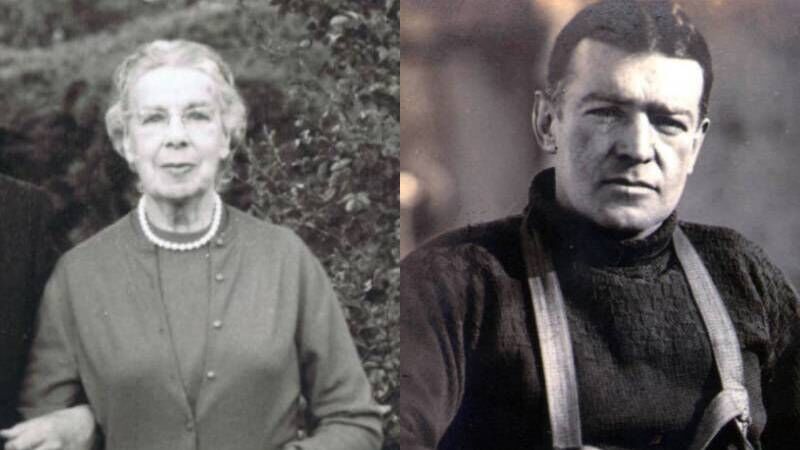

Her sister Kathleen volunteered to join brother Ernest on his final expedition, but Eleanor, above, was also a pioneer, nursing the war wounded across Europe and Canada.