Fergus Finlay: It may feel like the worst of times but we've much to be thankful for

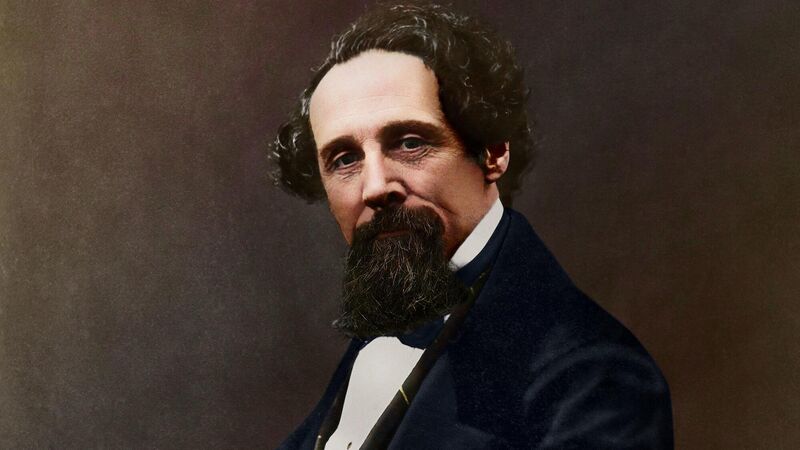

Throughout Dickens' life and his writing, Dickens’ central theme was the conditions in which people lived then. You can’t read about Tiny Tim or Smike in , or the workhouse experiences of , without realising that the phrase “the worst of times” was never far from Dickens’ mind. Picture: PA Wire

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, … it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us … I’m not talking about Covid-19, although maybe I could be. That’s part of the opening sentence of one of the greatest historical novels ever written, . It was written, of course, by Charles Dickens, who probably deserves a new place in history as the father and the founder of bingeing.

Are we all bingeing? I know we are in my house. There is no greater pleasure than finding a new series on one of the streaming channels, or on the RTÉ Player, that we can lock on to. You watch the first episode, and if you don’t abandon it there and then, you’re hooked. You just can’t wait for the next one.