The man Michael Healy-Rae wanted banned: Artist, critic and author Brian O'Doherty

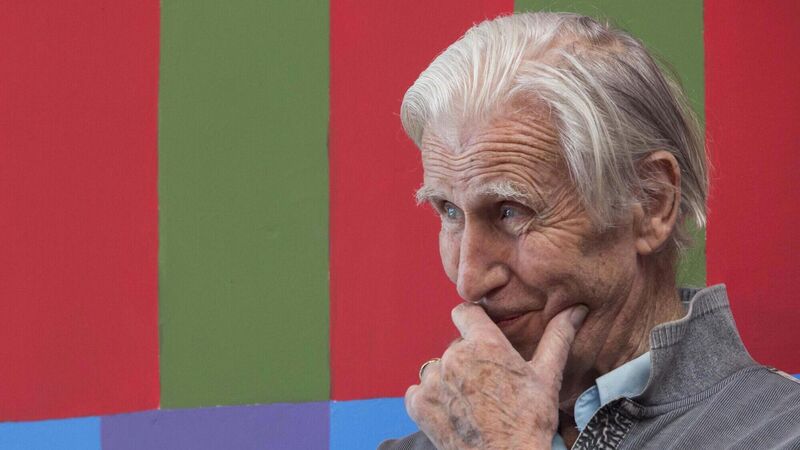

Brian O'Doherty qualified as a medical doctor before becoming an art critic, an artist, a television presenter, a filmmaker, an author and an educator. Picture: Clare Keogh

Brian O’Doherty, who died in New York on November 11, aged 94, was a native of Ballaghdereen, Co. Roscommon, who found fame as an art critic, an artist, a television presenter, a filmmaker, an author and an educator. This all came after he first qualified as a medical doctor.

Born in 1928, O’Doherty studied medicine at UCD before progressing to postgraduate studies at Cambridge and Harvard School of Public Health, where he made an unlikely career change in 1957.

He had always loved art, and in Harvard he found himself being invited to present an arts interview programme on Boston public television, succeeding the art historian Barbara Novak, who later became his wife. Among those he interviewed were legends of the visual arts world such as Josef Albers, Marc Chagall and Walter Gropius.

O’Doherty and Novak moved to New York, where he established himself as an art critic for the New York Times. He told the in 2010 how exciting it was to be in New York at that time: “The 1960s were incredible,” he said.

“There was violence, drugs and rock’n’roll, and there were many casualties, of course. But I was also fortunate enough to be in at the start of something, particularly in New York, when art was moving away from painting and sculpture and exploring other methods and other modes, like video.”

O’Doherty later edited specialist arts magazines such as Art in America and Aspen, and worked for the National Endowment of the Arts, the American equivalent of the Arts Council, where he served first as director of its visual arts programme and later as director of its media arts programme.

In this capacity, he created the long-running television series American Masters and Great Performances. He also served as Professor of Fine Art and Media at Southampton College, Long Island University.

O’Doherty also distinguished himself as an author. His best-known book of art criticism is Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space, published in 1976. His novels included The Strange Case of Mademoiselle P; The Deposition of Father McGreevy; and The Crossdresser’s Secret.

The Deposition of Father McGreevy caused some controversy when it was nominated for the Booker Prize in 2000. The book is set in Co. Kerry, and local politician Cllr Michael Healy-Rae, having read a 29-page extract, proposed that “a Muslim-style fatwa” be placed on its author because of the offence it was supposed to have caused to Kerry people.

He also called for the book to be banned, claiming it depicted Kerry farmers as “going around after sheep with their trousers down around their ankles, groaning and grunting behind bushes.” RTÉ's Liveline presenter Joe Duffy invited both Healy-Rae and O’Doherty on to discuss the subject.

After O’Doherty described Kerry as “a magical place” Healy-Rae rescinded the fatwa, saying of O’Doherty that “he seems like a nice fellow.” Contacted today by the , Healy-Rae said: “I have to be perfectly honest and say that I do not remember this debate. My head would be good but this is too far back.”

For all his success as a critic, author, educator and administrator, O’Doherty was always keen to be taken seriously as a maker of art. The most arresting of his early works was a piece he made In New York in 1966.

After inviting the veteran conceptual artist Marcel Duchamp to dinner one evening, he recorded Duchamp’s heartbeat, later exhibiting the electrocardiogram as part of a 16-part artwork he called Portrait of Marcel Duchamp. In so doing, he cheerfully subverted Duchamp’s contention that an artwork is effectively consigned to death once it is hung in a museum.

O’Doherty had an insatiable curiosity about the human condition, matched by a boundless capacity for work. He drew, painted, and made films, and created installations in art galleries around the world. Some of the best known were ‘rope drawings’, works in which he painted the gallery walls and ceilings. He had more than 40 solo exhibitions, including a number of major retrospectives.

In 1972, protesting the massacre of 13 civilians by British soldiers in Derry on Bloody Sunday, he assumed the pseudonym Patrick Ireland at a ceremony called Name Change, held as part of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art in Dublin. It was, he acknowledged, the gesture of an exile, but he resolved to sign all his artwork with the pseudonym “until such time as the British military presence is removed from Northern Ireland.”

As part of the ceremony, O’Doherty’s naked body was painted orange from the head down, and green from the feet up. As the colours merged, they turned a muddy brown; the artist later remarked that he looked like an atrocity victim.

It was not until 2008 that O’Doherty felt it appropriate to change back. On May 20, that year, he buried an effigy of Patrick Ireland in an elaborate ceremony on the grounds of the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, and resumed making art under his birth name.

In 2010, O’Doherty and Novak donated 76 works from their art collection to the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin. It included work by Edward Hopper, Christo and Jasper Johns. “It’s usually millionaires who make gestures like this,” O’Doherty told the at the time.

O’Doherty’s last major project in Ireland was Be Here Now in 2018, spearheaded by Miranda Driscoll, the then-director of Sirius Arts Centre in Cobh. O’Doherty and Novak had undertaken a residency in Sirius in 1995/96, and he had used much of the time to create a series of remarkable murals, inspired by Ogham script, all over the gallery walls. Cobh had been the point of departure for O’Doherty when he left Ireland for America nearly 40 years before.

The murals remained in place for a year before being covered up with heavy duty wallpaper to facilitate the gallery’s exhibition programme.

On taking the reins at Sirius in 2014, Driscoll discovered the murals were still intact. With O’Doherty’s support, she oversaw a restoration and conservation project which saw them being revealed once more.

O’Doherty and Novak flew in from New York for the unveiling, which coincided with his 90th birthday on April 20, 2018. One Here Now featured a busy programme of events, including a public interview with O’Doherty, exhibitions and musical performances, and a three-month screening of his films at the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork.

“I am now a saint,” O’Doherty said at the time. “I was canonised in Cork. This is my supreme narcissistic moment, in which my faith in myself is completely justified communally.” After a year, his murals were covered up again, this time with protective walls that should facilitate their exposure at some other point in the future.

Commenting to the , Driscoll said: “Brian O’Doherty was an artist of extraordinary multiplicity. Among his many contributions to the art world, he changed how art was viewed and experienced in the context of the gallery space. His legacy of an incredible life, well-lived, which spanned almost a century, will live on, long after we are gone.

"He himself was not a man to limit himself to any one identity, so I think he would enjoy that concept.”

Fiona Kearney, director of the Glucksman Gallery at UCC, has also paid tribute, saying: “Brian O’Doherty was an irrepressible provocateur in art and life and a joy to work with.”

Another paying tribute is Mary McCarthy, director of the Crawford Gallery: "He has had a profound effect on a generation of us, with his art, writings, film and performances. We are at Crawford grateful to Miranda Driscoll, former director of Sirius Art Centre, for bringing him to the Gallery in 2018.

"We will remember him for his work, but we also remember him for his wicked sense of humour, his warmth, kindness and most of all, attentiveness to all of us."

O’Doherty (1928 - 2022) is survived by his wife, the art historian Barbara Novak. The couple had no children.