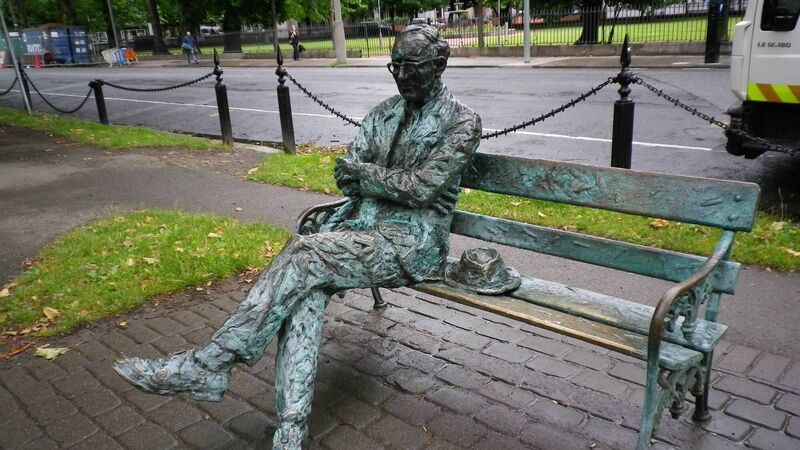

Personal Insights: Grieving for my mother with the ghost of Patrick Kavanagh

A statue of Patrick Kavanagh on the banks of the Grand Canal, Dublin

ODDLY enough, my first thought after I learned that my mother had been diagnosed with lung cancer last year was the Grand Canal in Dublin, even though I’ve never been there.

My mother was born in Dublin, but that wasn’t what I was thinking about. In my mind’s eye, I saw a man lying on the grass there, shoeless, sockless, screening the sun with a Panama hat.