Richard Collins: Irish team discover exciting basking shark fact

Basking sharks can be up to 12m long — they are the largest fish in the North Atlantic, and the second-largest worldwide. Picture: George Karbus

Basking sharks have returned to Keem Bay in Achill, where they were massacred decades ago. There was even a late sighting of one there two weeks ago.

Hunted for the oil in its liver, an liamhán gréine became scarce in Irish waters. But its fortunes have improved; it is being recorded increasingly off our west and southern coasts.

These gentle giants don’t conform to the usual notion of how sharks should look. They are not streamlined sleek and scary like the monster in . Lumbering juggernauts, basking sharks can be up to 12m long. These, the largest fish in the North Atlantic, and the second-largest worldwide, don’t really want to be sharks; they would much prefer to be baleen whales. Feeding on plankton, they swim along quietly, drawing water into their enormous gapes like giant vacuum cleaners, to filter out little creatures with their ‘gill-rakers’.

Not only are they harmless to humans, these fish will allow boats to approach them occasionally — a trait which has proved invaluable to Trinity College Dublin scientists who have been studying them.

Fish are cold-blooded, their body temperature being the same as that of the water around them. There are, however, some notable exceptions. Fast-moving athletic fish, such as tuna and the notorious mako and great white sharks, can generate their own body-heat. It was thought that only fish with ‘high-octane’ lifestyles needed to do this, but the TCD researchers have made an unexpected discovery. In a paper just published, they argue that basking sharks warm their body cores internally — a remarkable finding. Although these giants can move very quickly if the need arises, and they even breach spectacularly, their ‘normal’ lifestyle is leisurely and laid-back. Living on plankton, at the bottom of the marine food-chain, they don’t need agility to catch their prey.

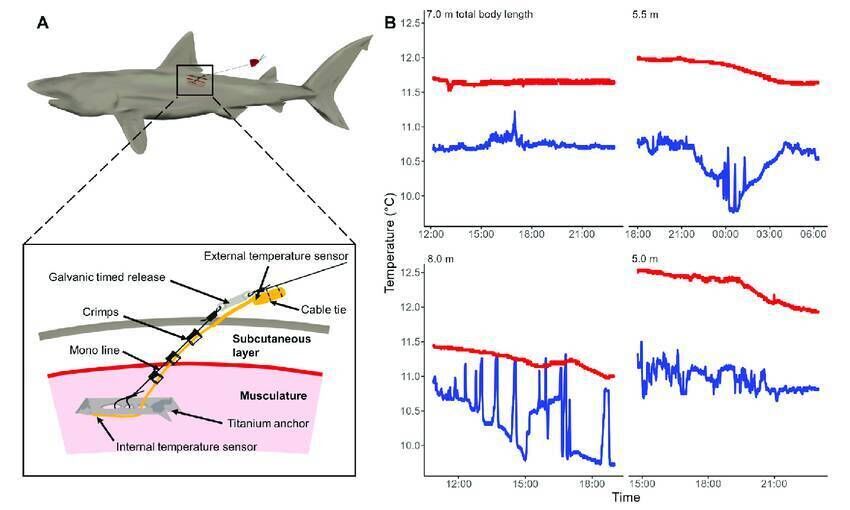

Haley Dolton and members of her team at Trinity sailed quietly up to sharks off the Cork coast. Then, using a long pole, they attached muscle-temperature recorders to the backs of the giants. The tags were programmed to detach automatically in due course and rise to the surface, where their bright red flotation devices enabled them to be spotted and retrieved for analysis.

The experiment showed that the body temperature of the giants is higher than that of the surrounding ocean. It is similar to that recorded for those shark species known to generate their own heat. Their ‘sub-cutaneous white muscle’ is ‘consistently 1.0° to 1.5°C above ambient’ according to the paper just published.

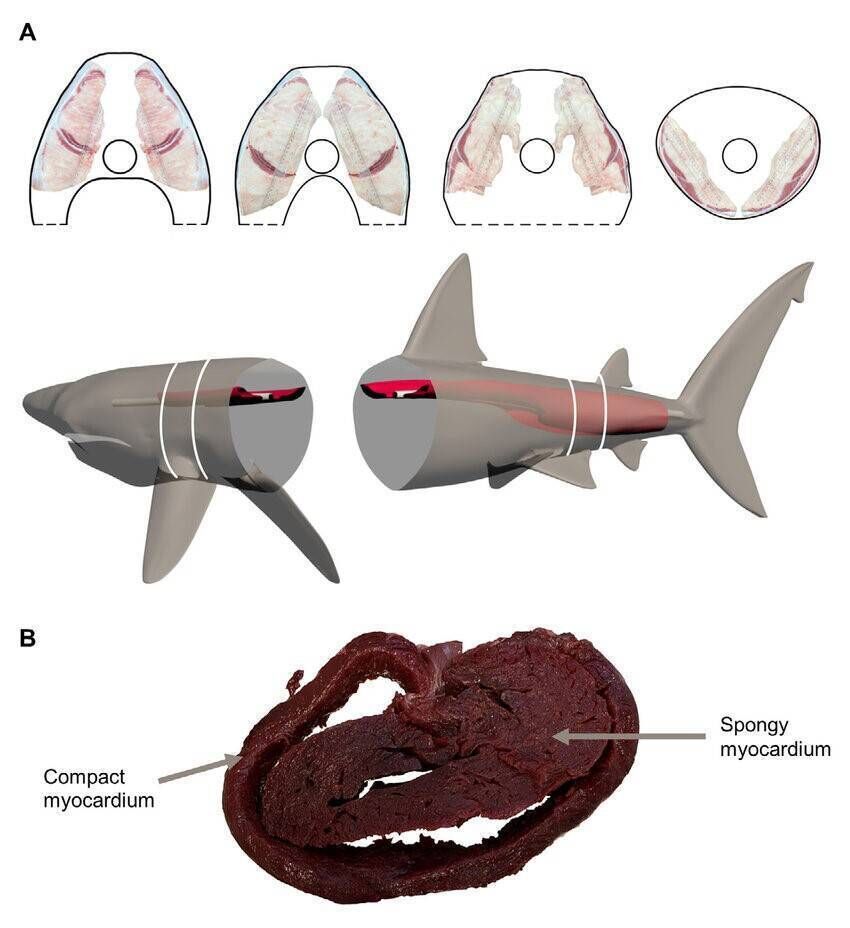

The carcasses of stranded basking sharks had been dissected. This confirmed that the species has the ‘centralised red muscle’ and the ‘thick-walled’ heart characteristic of warm-blooded fish.

These results have put the cat among the proverbial marine pigeons. The idea that only fast-moving predators can generate their body heat internally is now dead in the water. "It’s a bit like suddenly finding that cows have wings," declares senior author Nicholas Payne on the Trinity website. We will have to "adjust our assumptions about the advantages of such physiological innovations for these animals".

The Trinity results may help solve some of the many mysteries surrounding this mysterious beast.