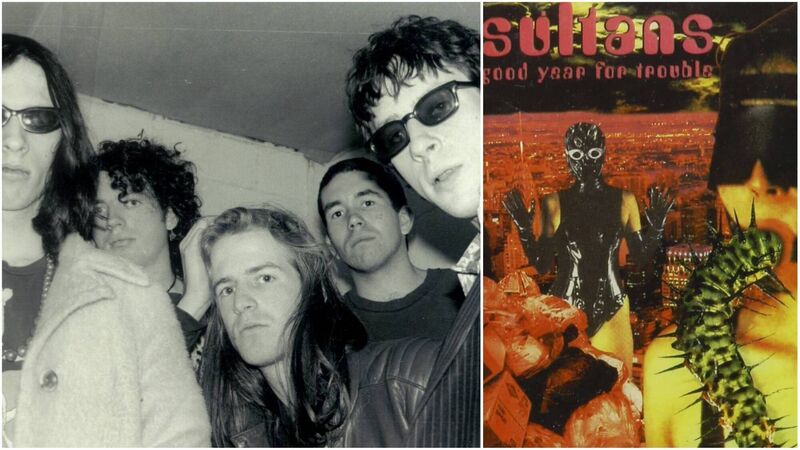

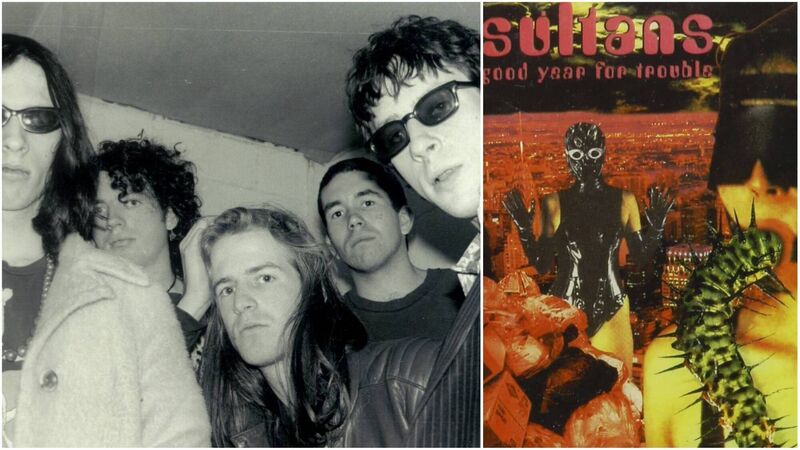

Ireland in 50 Albums, No 1: Good Year For Trouble, by the Sultans of Ping

Good Year for Trouble by the Sultans of Ping

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Good Year for Trouble by the Sultans of Ping

It's alright to say things can only get better – but by 1996 the lights were going out one by one for Sultans of Ping.

After years of success, the band were watching their career unravel one stitch at a time, as sales dipped and column inches shrank. And then came the final blow: an American tour that never was.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.

Newsletter

Music, film art, culture, books and more from Munster and beyond.......curated weekly by the Irish Examiner Arts Editor.

© Examiner Echo Group Limited