All in the gutter: 10 graphic novels with star quality

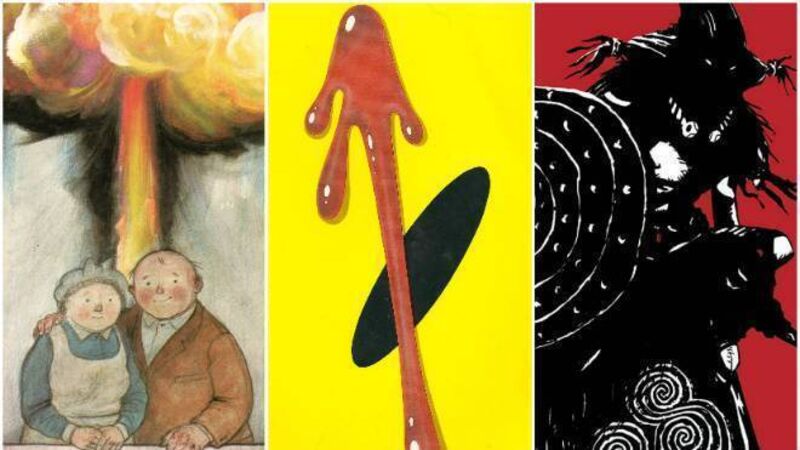

Some of Don O'Mahony's graphic-novel classics

The notion that comics are 'just for kids' has become increasingly old-fashioned and when news emerged earlier this year that the board of trustees for McMinn County Schools in east Tennessee voted unanimously to remove the Pulitzer Prize-winning from the curriculum it suggested that this illustrated story was too dangerous for younger readers.

Comics clearly deal with a range of complex subjects, so here is not necessarily a 'best of' list, but 10 worth considering for the times we live in.