Marley and me: Irish people share their memories of Bob Marley and his one visit to Dublin

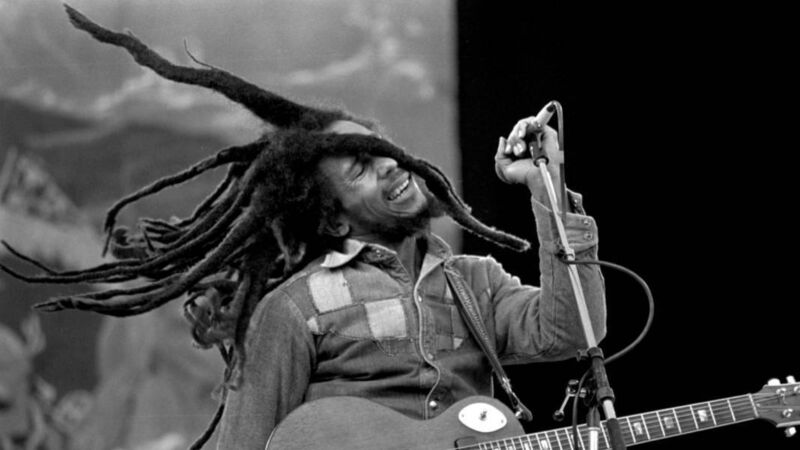

Bob Marley at Dalymount Park. Picture: Eric Luke

(Bob Marley's last outdoor concert before his death at the age of 36 was at Dublin’s Dalymount Park, Sunday, July 6, 1980. It was a sunny afternoon gig in which he referenced “the Irish struggle” before performing Redemption Song.)