Slaves to the rhythm: 100 years of the robot

Giving a helping hand.: Stevie II, Ireland's caring robot was well-received when tested in nursing homes in 2019.

Today's robots control driverless cars, and guide rovers on the surface of Mars. Hospitals rely on them to help with surgical operations. Thanks to them, in many homes, floors are vacuumed without our assistance. The latest can even shop for people unable to get out and remotely treat coronavirus patients.

Self-operating mechanisms have appeared since ancient times in Chinese, Greek, Egyptian and Jewish cultures, but the word ‘robot’ only came to public notice in the 20th century.

Although its origins can be traced to the old Slavic term 'robota', meaning serf labour, it was Czech dramatist Karel Čapek who first used the word in print.

In his play RUR (Rossum’s Universal Robots) 'A Fantastic Melodrama', published in 1920, a factory, set on a distant island in the future, uses a secret chemical substitute for protoplasm to manufacture artificial people called 'robots' and 'robotesses'.

Priced at $150 each, and with a life expectancy of 20 years, Rossum’s claim that their human-sized creatures provide “the cheapest workforce” available.

“Even with its food, a robot costs no more than three-quarters of a cent per hour!” Čapek's robots eventually take their revenge: they rise up and kill their human creators.

At the end of the same decade in which the play appeared, robots began to move from science fiction into the real world.

Golden-skinned Gakutensoku (Japanese for “learning from the laws of nature”) was built in Osaka in 1928. Biologist Makoto Nishimura intended that his robot should be a free, aesthetic being, not one of Čapek’s slaves to industry.

Operated by air pressure, springs, and gears, it could change facial expression, raise its eyelids, move its hands and head, and puff out its rubber cheeks.

Perched on top of this towering 3.2 metre mechanical wonder was a bird-shaped robot named Kokukyōchō ("bird that tells dawn has broken"). When Kokukyōchō cried, Gakutensoku's eyes closed and its expression became pensive.

In the giant’s right hand was poised an arrow-shaped pen, and its left hand held a lamp named Reikantō ("inspiration light"). When the lamp shone, Gakutensoku used the pen to write – in beautiful Chinese script.

Gakutensoku wowed spectators in Japan and Korea but was lost while touring Germany in the 1930s.

Today, an asteroid is named after the robot.

Elektro made its debut at the World’s Fair in New York in 1939, introducing itself to crowds with the words: “Ladies and gentlemen… I am a smart fellow as I have a very fine brain of 48 electrical relays.”

The 2.1 m-tall steel and aluminum sensation could 'walk' (its left knee bent and right leg is drawn behind), twist its head and arms, 'speak' about 700 words (using a record player), and sing.

It told lame jokes, could drag at cigarettes and puff out smoke, and would challenge spectators to balloon-blowing competitions which it generally won.

In 1940 it reappeared with Sparko, a robot dog that could bark, sit and beg.

Although dismantled in the 1960s, Elektro was pieced back together and is on show today at the Mansfield Memorial Museum, Ohio.

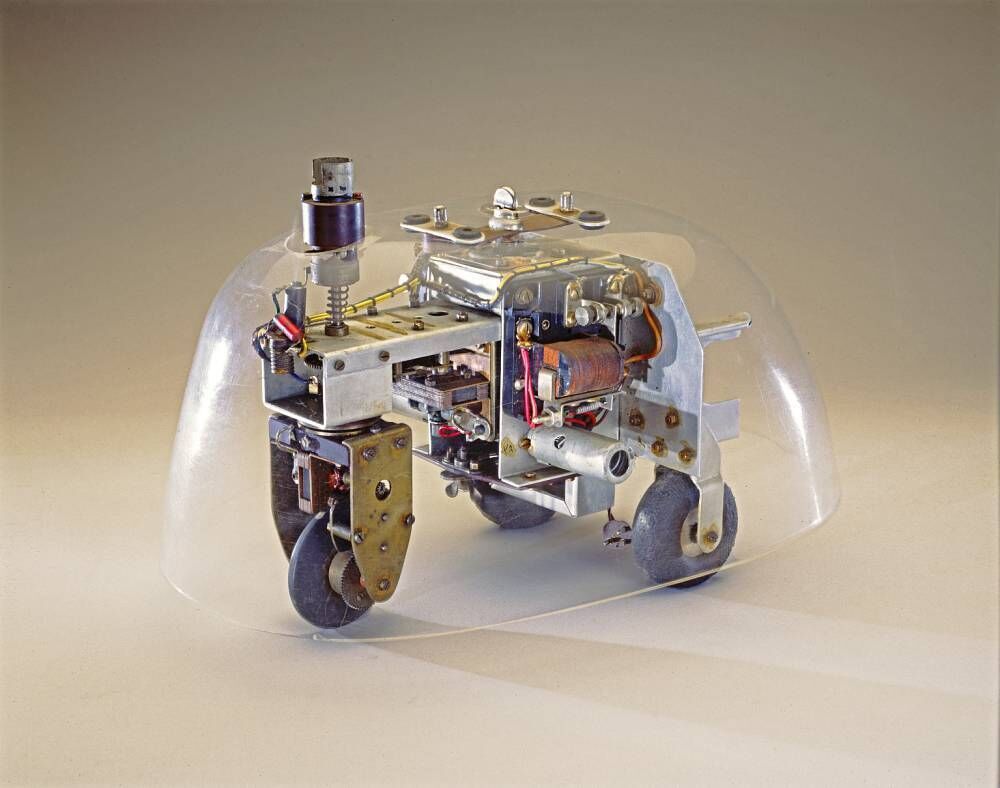

Tricycle-shaped robots Elmer and Elsie were built in 1948-49 by neurobiologist William Grey Walter, using leftover materials from the War, and a few old alarm clocks.

Their round plastic shells, and the way they wandered slowly around the floor, quickly earned them the nickname 'tortoises’.

The robots explored their environments as systematically as animals and moved towards light sources at every opportunity.

When put in front of a mirror, they began "flickering, twittering and jigging" —which Walter claimed was evidence of self-awareness.

Eventually, Elmer and Elsie were taken to bits, and six other robots built from their parts.

In 1974 Michael J Freeman created a 1.7m-tall, 91kg humanoid teacher called Leachim.

After being programmed with a curriculum, and background information on forty 4th grade pupils, it was tested in a classroom in the Bronx, New York.

The robot spoke in an understandable way, and showed "infinite patience". Pupils found lessons “personal, exciting and rewarding”.

In 1975 Leachim was stolen from the truck transporting it back to New York after appearing on a TV show in Chicago.

Wabot-2, constructed in 1984 at Waseda University, Japan, was able to move its arms and legs more freely than any other robot then in existence.

Built with fingers, feet, an eye, a mouth, and ears, it could read a musical score and tap softly on the keys of an electronic organ to play tunes of “average difficulty”. This 'specialist' robot could accompany a person singing and adjust tempo accordingly.

Stevie II, well-received in Dublin nursing homes when it was tested in 2019, has hands to turn on the television and control the lights and thermostat.

It can give a reminder when medicines should be taken, run quizzes, and offer video-calling from a screen built into its head.

Whereas Amazon's Alexa relies on audio signals — useless for the deaf — Stevie II can make facial expressions and perform gestures: a sophisticated creature, light-years away from Čapek’s soulless, unsmiling brutes 100 years ago.