CNN had a problem... President Donald Trump helped solve it

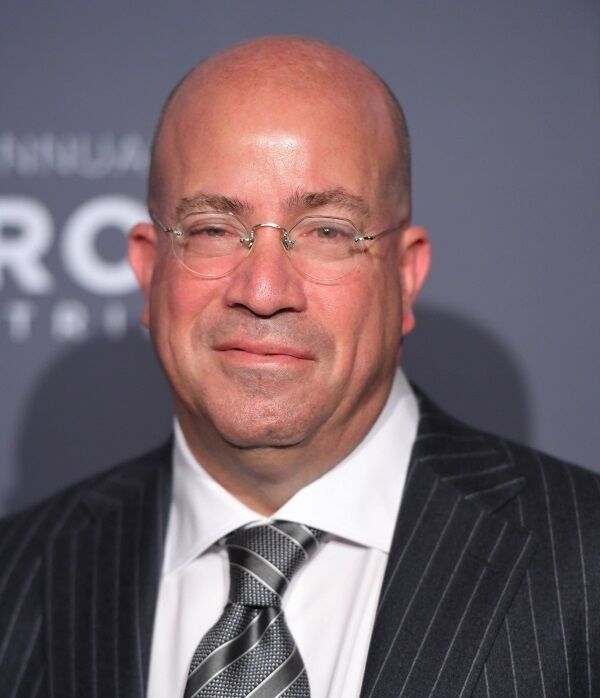

At 3.58pm on a recent Wednesday afternoon in Washington, the largest control room of the CNN news channel was mostly empty, but for a handful of producers hunched over control panels and, hovering behind them, a short, barrel-shaped man in a dark pinstriped suit: the president of CNN Worldwide, Jeff Zucker.