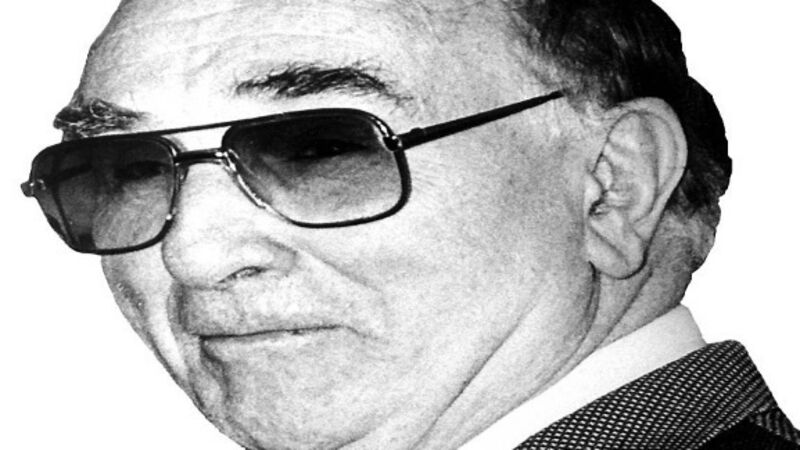

Seán Feehan of Mercier Press: The man who defied the odds to tell the stories of Ireland

The last week in May is the 25th anniversary of the death of Captain Seán Feehan, who founded Mercier Press, in Cork, in March, 1944. He had a profound impact on Irish book publishing.

Feehan began publishing while serving in the army. Initially, publishing was little more than a hobby. He started, he said, on “a wing and a prayer”, by publishing The Music of Life, by James O’Mahony of University College Cork.