Robot rugby may be a way off but art of coaching is making way for science

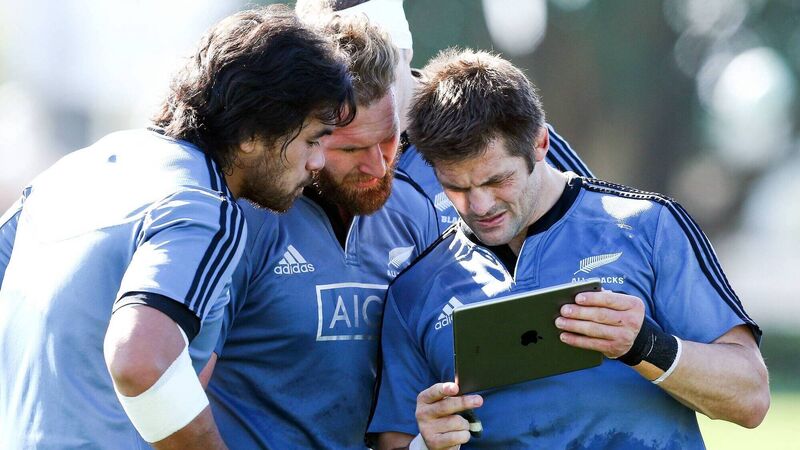

TECHNOLOGY: L to R, Steven Luatua, Kieran Read and Richie McCaw look at an iPad during a New Zealand All Blacks training session. Pic: Hagen Hopkins/Getty Images

Once upon a time coaching sport was deceptively simple. Many years of experience could be distilled into a gut instinct of how best to respond in certain situations. Selection was more of an art and less of a science and you didn’t have smarty-pants analysts telling you stuff that – damn it! – you could already see with your own eyes from 50 yards away.

Pray for the old-timers because rugby’s tech era is well and truly here. Nowadays, one game spawns millions of pieces of usable data. Wearable technology attached to one player can collect information from 300 data points at a rate of 40 times per second. Skeletal tracking, microchipped balls – less painful than it sounds – and myriad other previously invisible markers are now routinely available. Farewell, then, leaky Biros and old‑school clipboards.