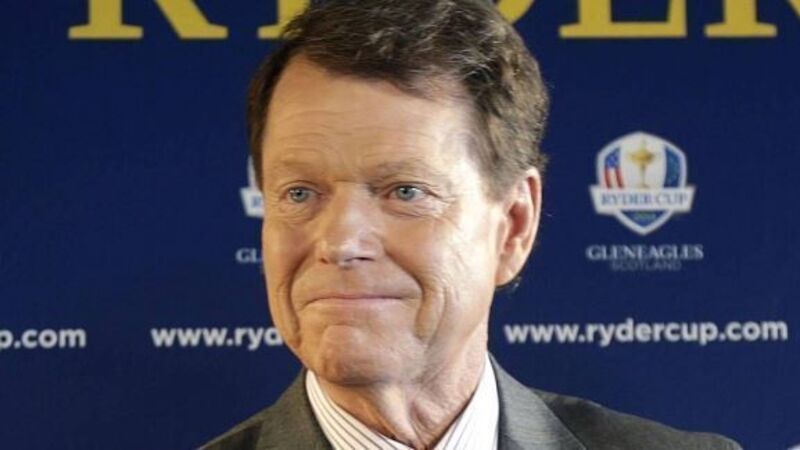

Jim McCabe: Tom Watson’s admirable legacy

He said it was okay to concede our American ignorance about links, that it was not a sign of weakness to say that we didn’t like what we didn’t know. But so, too, did Watson teach us that it didn’t have to be at first sight, that love could come, with patience, understanding, and admiration.

It had to be a give-and-take relationship, however. You had to give up your biases. You had to take time to study.