Enda McEvoy: Reliving five of Waterford's greatest days

The afternoon they became a modern hurling power.

In order to talk about Waterford’s Year Zero, however, one must first refer to the preceding season, Gerald McCarthy’s first in the job.

They hadn’t fared badly, running Limerick to six points in the provincial semi-final after replacing their goalkeeper before the interval. It was a start but it wasn’t anywhere near half the battle.

They knew they had to get fitter and hardier and they did.

The following December and into January they embarked on a training programme the likes of which, says the team’s coach Shane Ahearne “had never been seen in the county”.

Skills work in Fenor every Sunday morning was followed by fitness work in the sand dunes in Tramore, 10am to 2pm. Ridiculously punishing but they all bought into it and the sense of accomplishment was heady.

During the National League of 1998, the team and management also embraced the Nutron diet, then in vogue, and the chat in the cars on the way to training was suddenly all about the optimum methods of cooking pasta. After a number of weeks on the diet, Gerald McCarthy told them they could have a few pints if they won their next match against Laois, who were nobody’s eejits at the time. Laois 1-9 Waterford 4-11.

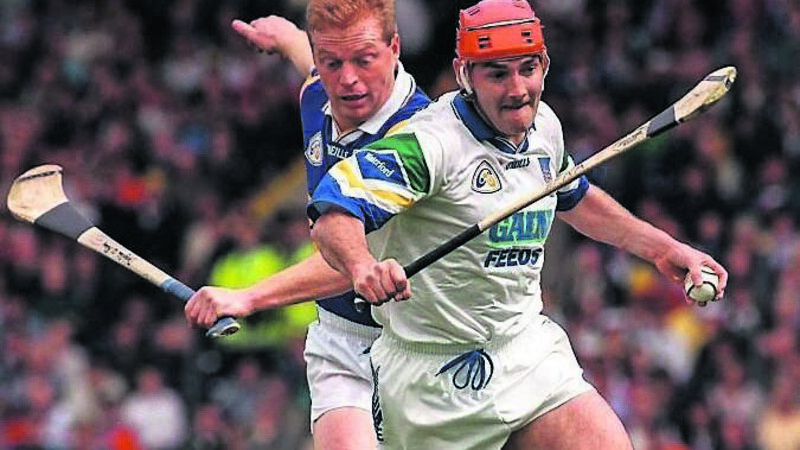

After reaching the league final and escaping from Tralee with a flattering eight-point win in the Munster quarter-final, the prospect of a gloriously extended summer rested on their meeting with Tipperary – who, they learned, were to deploy Declan Ryan at top of the right in order to exploit a supposed size advantage against Brian Flannery.

Waterford came up with their own cunning plan.

They instructed their defenders to stand in a bunch during the preliminaries until the Tipperary forwards took up their positions, upon which Tom Feeney trotted over to mark Ryan.

Stephen Frampton left a calling card of his own, creasing John Leahy with a shoulder that may have been felt back in Mullinahone.

Tipp were betwixt and between, marking time between the Babs Keating era and the team of 2001. They led at the break by 1-10 to 0-8 but didn’t score for 20 minutes on the restart.

Waterford, patently the better side, clocked up half as many scores again as their opponents and they didn’t feel the need to use a sub.

Victory was sealed when Dan Shanahan grabbed a puckout from Brendan Landers and slung one over from right on the touchline under the old stand.

Waterford were into the All-Ireland series for the first time since 1963. Suckin’ diesel at long last.

Did they really believe they could inherit the earth?

During Colm Bonnar’s incarnation in the blue and gold, nobody had ever doubted. They were Tipperary. Now that he was on Justin McCarthy’s coaching staff he found the same unquestioning dogma didn’t exist.

They were Waterford.

“One night in the dressing room the question came up about who’d win the Munster championship. Only a few people put up their hands to say Waterford. I was left thinking, what are we training for then?

“But we were lucky in two ways. Gerald McCarthy had done great work putting in a foundation. After the two Munster final disasters of 1982-83 the club scene in Waterford had become more important than the county. Gerald brought the passion for the county back. Then we had guys like Stephen Frampton, Fergal Hartley, Peter Queally. Terrific leaders. They’d die for the jersey.”

They also had Stephen Brenner and his puckouts. Now Brenner’s puckout wouldn’t occasion comment in today’s world, where every goalie possesses a siege gun made of ash.

But back then Brenner could hit the half-forward line with his clearance, a feat worthy of comment. With the Munster final delicately poised – the underdogs doing most of the hurling, the favourites hanging in there doggedly thanks to two goals from Benny Dunne – Brenner went long off the tee.

The ball skittered through the ruck of players gathered on the Tipp half-back line. And lo, there was Tony Browne, the ultimate box to box midfielder, tearing beyond the cover and with a swift, clean ground stroke slipping the sliotar past the outrushing Brendan Cummins. From there on it was a one-horse race.

“The last 20 minutes, it was like a train coming,” Bonnar recalls. “In the circumstances nobody would have complained had Waterford fallen over the line with a last-minute goal, but we hurled brilliantly. That made it even more special.”

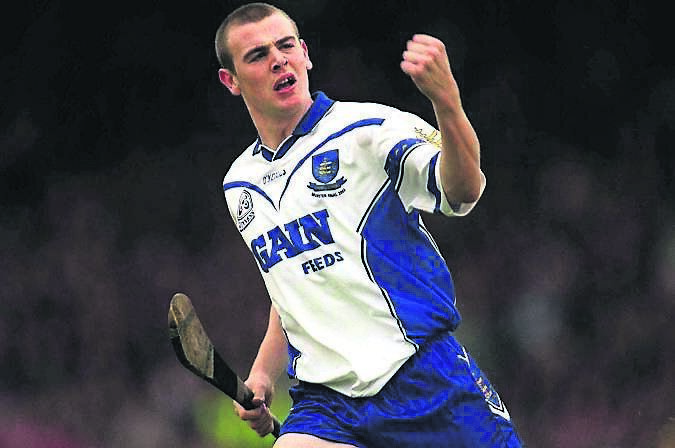

Reflect on that tally of 2-23 (K McGrath 0-7, J Mullane 0-4), seriously impressive for the era and against the MacCarthy Cup holders to boot.

Ken McGrath: “Even though it was the start of a new team it would have been the end of a lot of lads if we hadn’t won. We’d been there for four years at that stage and apart from 1998 we hadn’t been reaching Munster finals, meaning we hadn’t been reaching the All Ireland series. That Munster final, we had to win it.”

Waterford were Munster champions for the first time since 1963. On the way home they got off the bus outside Youghal, walked across the county border and stepped into a new version of themselves.

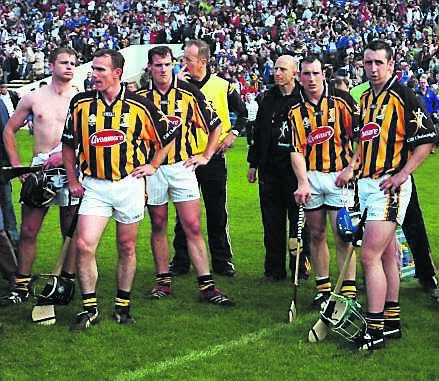

Granted, the usual caveats were applicable, as ever when it comes to a league final. Kilkenny had won the previous two renewals of the competition and would from now on be more interested in MacCarthy Cup sequences and general world domination; a measure of their lack of urgency could be gleaned from the sight of Cha Fitzpatrick at full-forward.

But Waterford weren’t busting a gut either.

They’d won two Munster titles; they’d been denied a replay in the previous year’s All Ireland semi-final by the telescopic left arm of Dónal Óg Cusack; the only piece of silverware they were interested in was the one presented on the steps of the Hogan Stand in September.

They were, in short, well past the stage of requiring a springtime hit of the bong to boost their self-esteem. There was, then, a pair of them in it.

Here’s something else. Waterford won this by mugging Kilkenny, having trailed by a point with five minutes remaining. That’s worth remarking on because, well, wasn’t it supposed to be the other way around? The new champions were far from brilliant yet they got there in the end. What a comment on their progress since 1998.

The comeback featured an incident one wouldn’t see now. Brian Hogan, with time and space on his hands, chose to pull on the sliotar instead of lifting it. He shanked his effort straight to the hitherto anonymous John Mullane, who put the sliotar between the uprights at the Town End. The real hero of the endgame, though, was Seamus Prendergast, who twice went to the skies to grab a dropping ball and score.

Kieran O’Connor has been commentating on Waterford matches for WLR FM since 1992. This was the first time he’d seen them take national honours.

“After all the disappointments in semi-finals, it was a great feeling. And beating Kilkenny made it even sweeter. I wouldn’t say there was a fear factor beforehand but there was definitely a nervousness. But when push came to shove, Waterford’s big men stood up. It made me believe. I thought to myself, ‘God, the big one is on now.’”

“A fantastic day for hurling,” declared uachtarán Nickey Brennan as he handed the trophy to Brick Walsh.

Waterford were National League champions for the first time since 1963. They would never be better – never more expansive, never more swashbuckling, never more joyous to behold - than they were in 2007.

It still didn’t suffice.

They were the underdogs. That was only logical. Tipperary were the new Munster champions.

Tipperary were the new National League champions. Tipperary had a vibrant young team, with a chap called Seamus Callanan at right-half forward, under an impressive young manager in Liam Sheedy.

The Deise? They’d deposed Justin McCarthy in a show of player power after flopping against Clare, installed Davy Fitz – one of the most improbable candidates imaginable to anyone who could recall the pandemonium of the summer of 1998 – and had huffed and puffed their way through the back door. Talking of improbable candidates, they also had Ken McGrath (Ken McGrath!) at full-back (full-back!), not making a particularly good fist of it and not enjoying a moment of this deeply strange exercise that pitted him against bustling full-forwards like Joe Bergin and Stephen Banville.

Had to be Waterford then, hadn’t it?

Actually, there was one good reason why. They had momentum generated by their circuitous route to Croke Park whereas Tipp had been idle for the previous five weeks. Besides, if the law of averages counted for anything, were Waterford really going to make it six All Ireland semi-final defeats from six?

“You know it doesn’t make sense…but underdogs to have their day,” ran the headline in the Sunday Tribune. (The other pundit to opt for Waterford was Jim O’Sullivan in this newspaper.).

Davy had taken his new charges off to Clare the previous weekend. They stayed one night in Doonbeg and another in Dromoland Castle, real fag end of the Celtic Tiger stuff.

Eoin Kelly was flying in the practice matches and destroyed McGrath. Davy and his selectors had the good sense to cut their losses on the experiment.

Waterford, with McGrath restored to centre-back and hurling like a man sprung from jail, hit the ground running the following Sunday, as their momentum entitled them to, and promptly went six points to nil ahead before Tipp gradually sloughed off their staleness.

Kelly and Callanan exchanged goals within a minute of each other entering the closing quarter but the men in white and blue managed the endgame better.

Ken McGrath: “I was confident. Any All Ireland semi-final we played, we felt we could win it. We’d shown great heart and spirit every year to come back. And we always performed in All Ireland semi-finals. Look at what was in it at the final whistle in all of those games.”

(Indeed: a point in 1998, three points in 2002, three in ’04, one in ’06 and five in ’07 following the concession of five goals.) Waterford were into an All-Ireland final for the first time since 1963. They didn’t realise it but, like your woman at the end of Brighton Rock, they were walking rapidly towards the worst horror of all.

At half-time in the New Stand toilets that sunny Saturday evening a man from Mullinavat fell into conversation with two Waterford supporters.

They were both of a certain age. They were both called John. They’d both been at the 1959 All-Ireland replay.

They hadn’t seen their county beat Kilkenny in the championship in the meantime. They were hopeful the great day had arrived but bitter experience ensured they couldn’t be confident about it. Their new friend from south Kilkenny wished them luck and went on his way.

Bitter experience also ensured that the Waterford players would at least leave everything behind them on Tom Semple’s field.

They’d out-hurled the men in stripes everywhere bar the scoreboard in the All-Ireland semi-final the previous August only to be caught on the finishing line, then gone blow for blow with them in a tumultuous replay only to fall short by two points after Eoin Murphy had done a Dónal Óg to Pauric Mahony.

Tactically they’d learned from the heartbreak. Conor Gleeson affixed himself to Richie Hogan, who’d scourged Waterford with 11 points over the course of the two games in 2016. Philip Mahony took TJ Reid.

Brick Walsh was told to get into the danger area more. Jamie Barron was instructed to bomb on from midfield as often as possible.

For an hour it all worked beautifully. Walsh scored a goal and created another for Shane Bennett. With ten minutes remaining Derek McGrath’s charges led by 2-15 to 1-10 and were worth every score of it. Predictably, despite their abundant limitations, Kilkenny had a kick left in them. They reeled off an unanswered 1-5, the goal a pushover try by TJ Reid, to bring proceedings to extra time.

McGrath and his selectors were flummoxed momentarily. What the hell were they supposed to do now?

They discussed bringing back on Bennett and Brick before, in a lightbulb moment, concluding that to do so would undermine all that they’d preached about the primacy of the panel.

Instead, they chose to keep faith with the marksmanship of Maurice Shanahan and the legs of Brian O’Halloran and Tommy Ryan. All three delivered, Barron steamed through for the game-breaking goal and Shanahan batted home the fourth.

“Enough was enough,” Derek McGrath reflects. “This time we had to win. No near-misses, no moral victories. The players piled the pressure on themselves – and they delivered.” Waterford had beaten Kilkenny in the championship for the first time since 1959. And the two Johns went home feeling like young lads again. And the chap from Mullinavat, though far from overjoyed himself, went home feeling happy for them.

Five groundbreaking Waterford performances. Kieran O’Connor was the man behind the mic for each. One last piece of ground remains to be broken by Waterford and thus by him.

Maybe next Sunday.