Bloody Sunday: An illustrated guide to a murderous countdown to carnage

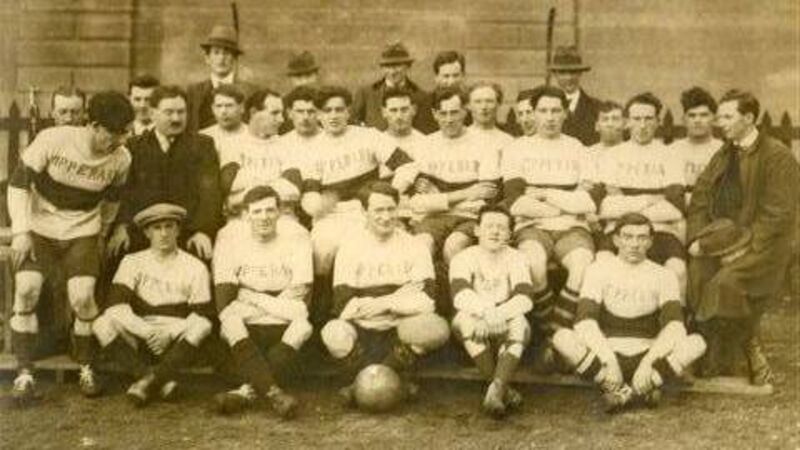

THE story of ‘Bloody Sunday’ does not begin on the day itself. It does not start on November 21 when this photograph of the Tipperary footballers was taken at Croke Park. For the GAA, no more than for others caught up in the carnage of that day, the story begins some weeks before.