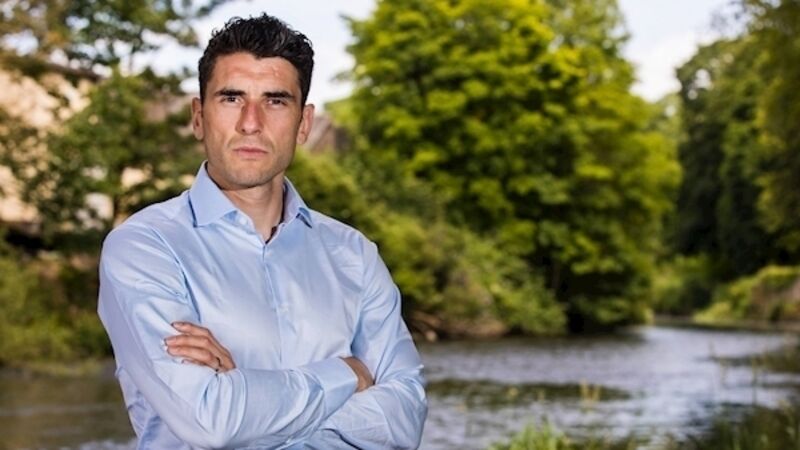

Bernard Brogan: ‘You’d always think that you’d get another chance’

After more than two years of constantly being asked about and reminded of his place on the margins of the Dublin panel, there’s been something refreshing and comforting in recent days for Bernard Brogan that people haven’t forgotten when he was king of the Hill and just about everything else in football.

The recent re-appreciation began with Jim Gavin.