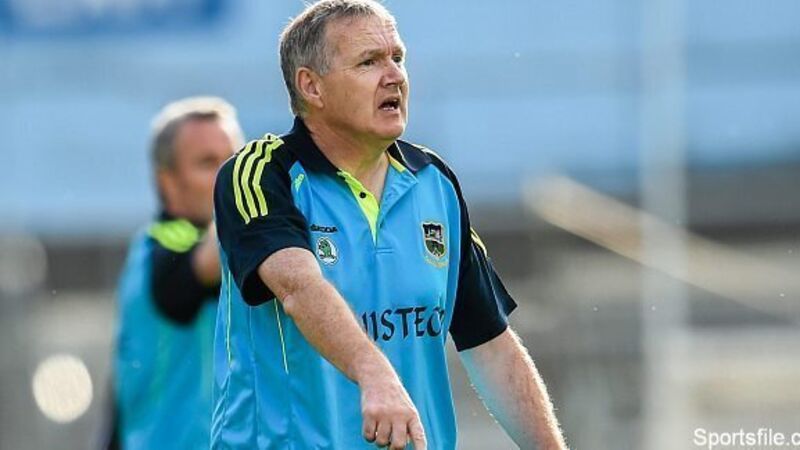

The big interview: Eamon O’Shea

Eamon O’Shea doesn’t get offended when you ask him to define what it is he does. He’s an economist who specialises in... well, let him explain.

“It’s gerontology, a way of looking at how ageing and an ageing population impact on life — community life, public spending, all of that. What I do is look at ageing in a social and economic context: social gerontology.”