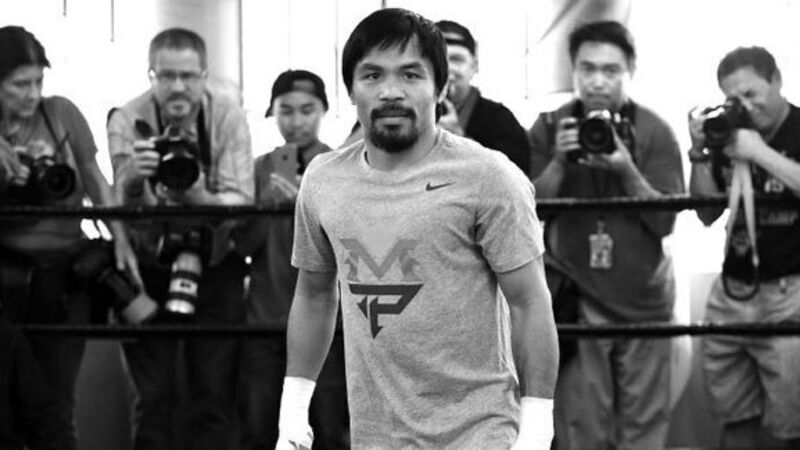

Godfather carries hopes of a nation

In its halcyon heyday, this corner of chaos carved out of the desert was home to a whole other kind of mob, one now confined to Hollywood’s halls of memory.

But yesterday, Las Vegas was again reverberating to the beat of the godfather.