Enda McEvoy: Shefflin controlled the controllables — now Galway must learn to do the same

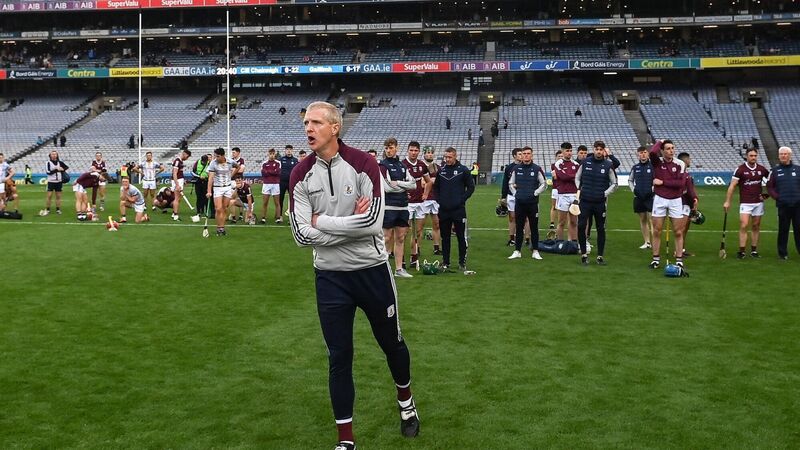

Leaning into the pain: Galway manager Henry Shefflin after the Leinster GAA Hurling Senior Championship Final match between Galway and Kilkenny at Croke Park in Dublin. Pic: Ramsey Cardy/Sportsfile

The money shot in the Leinster hurling final materialised not ten minutes afterwards, following the winning manager’s triumphal procession of half the field, but three or four minutes from the end when the RTÉ cameras zeroed in on his opposite number.

There was Henry Shefflin standing on the sideline as though turned to stone. Looking hunted. Looking haunted. The real money shot.