Enda McEvoy: Was Limerick's the ultimate All-Ireland performance? Short answer, yes

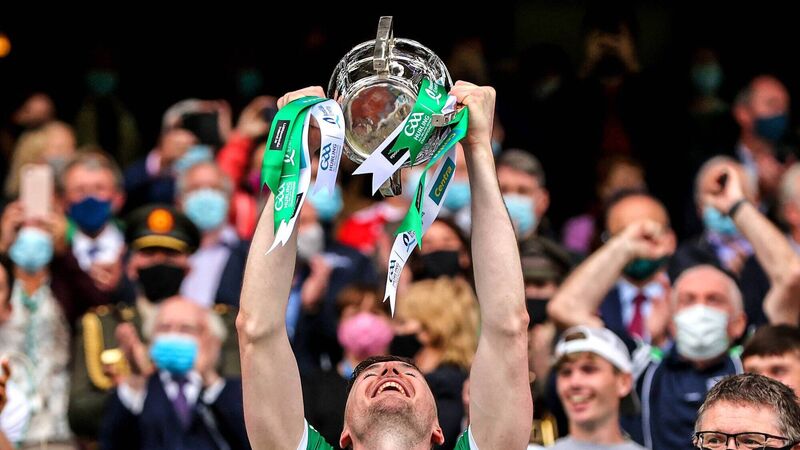

HIGH POINT: Limerick’s Declan Hannon lifts the Liam MacCarthy Cup at Croke Park.

We all know what we saw yesterday but occasionally it takes an outsider to put a different gloss on these things. Step forward Danny Kelly.

Danny, for readers unfamiliar with the great man and his oeuvre, was born in London. He’s the former editor of the NME and Q, has hosted many a sports chat show on radio and these days is domiciled amid the bucolic Barrow beauty of the Carlow/Kilkenny border, from where he watched the proceedings.