Kieran Shannon: GAA must realise water breaks are actually good for Gaelic games

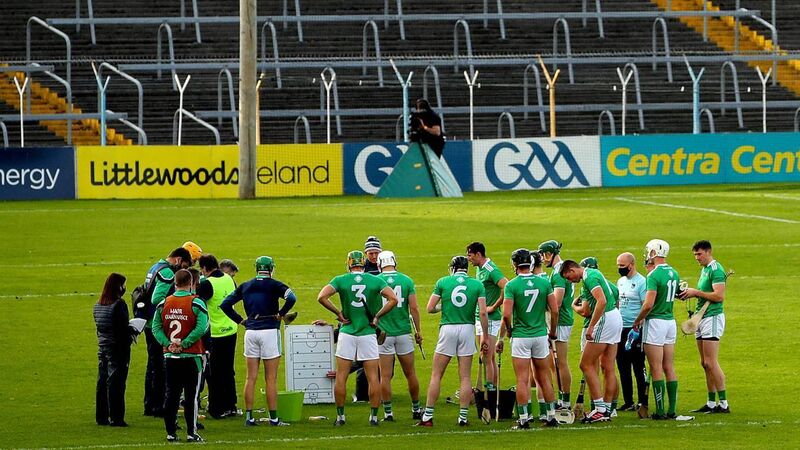

One newspaper columnist’s opposition to the development was based on the sight of Paul Kinnerk’s tactics board and how it was “as much a tactical break as anything” else like taking a swig of water. Picture: INPHO/Ryan Byrne

In spite of all the times we’ve heard the moans of a game being “lost on the line”, we’re hearing a fair share of people bemoaning anyone trying to coach on the line at all.

With the championship on our doorstep and the clubs back in action, some familiar heckles about the water break have returned as well.