John Fogarty on Bloody Sunday: Winter Championship an ode to the game that didn't finish

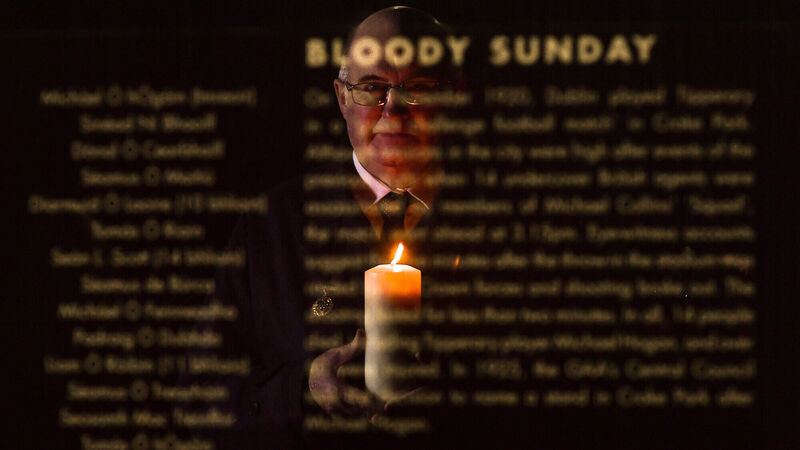

GAA president John Horan lights a candle at the Bloody Sunday memorial in Croke Park. In lieu of a larger commemorative event at Croke Park, the GAA is encouraging members, supporters, and the wider public to light a candle at dusk next Saturday, remembering the 14 people who lost their lives that day 100 years ago.