Kubrick's world may come true if we can unlock human hibernation

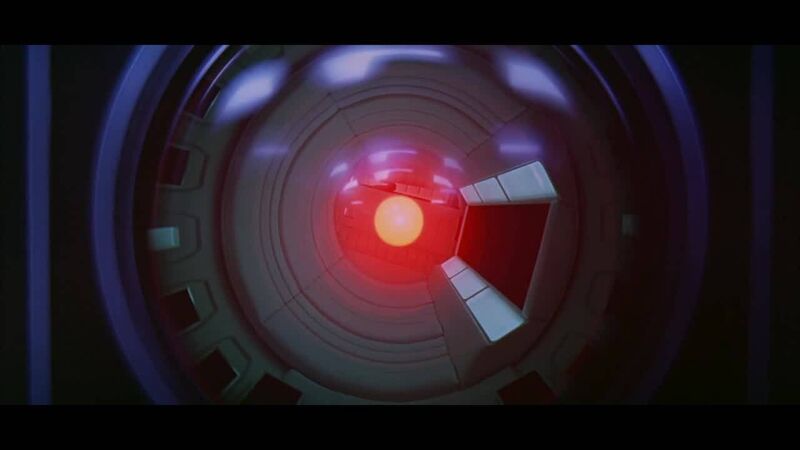

HAL the computer from 2001 Space Odyssey.

In Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film, passengers on a spacecraft travelling to Jupiter are in artificial hibernation, controlled by Hal, an all-knowing computer. Hal went mad and killed his charges.

It’s been suggested that Europa, one of Jupiter’s 79 moons, may be close to habitable, but to find out if it is, scientists will have to go there. This would involve a two-year journey each way, during which those on board the spacecraft might be put into hibernation under Hal’s successor.