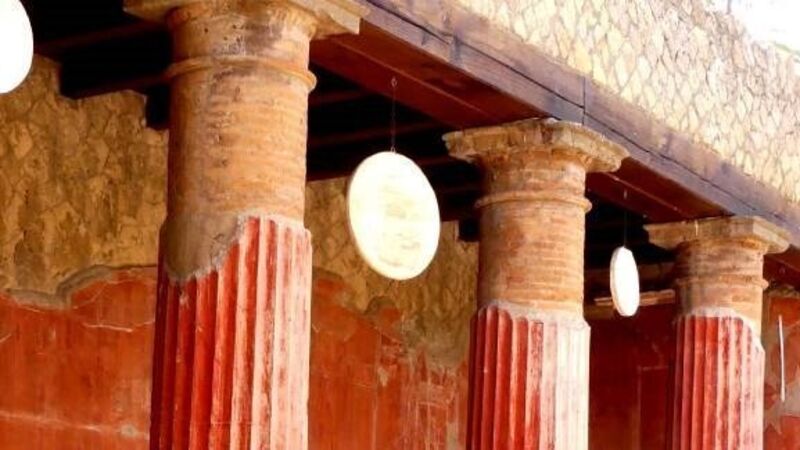

Vintage View: Pompeii second to the intimate wonders of Heraculaneum

AWESTRUCK — the word comes over as jaded, commonplace aggrandising. However, I found myself dashing away tears on a visit to Pompeii’s less discovered, compact neighbour: The ancient city of Heraculaneum in the suburbs of Naples.