Birds returning to make Ireland home

They too had been persecuted to the brink of extinction. Then, in 1933, a single pair bred in Antrim. Nobody is sure what inspired them, but birds from Ulster’s tiny relict population set out, like the missionaries of old, to reclaim their lost heritage. Buzzards now occupy the eastern two-thirds of our island, even challenging the sparrowhawk’s claim to be the commonest bird of prey in some areas.

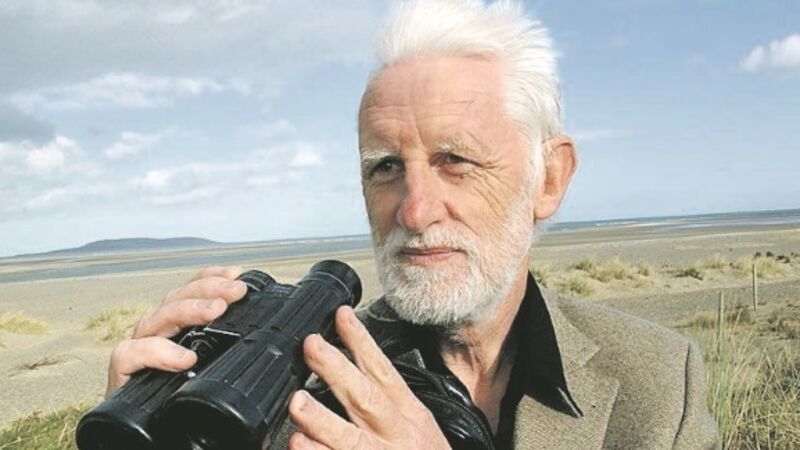

Meanwhile, another glamorous exile has returned; it is over a decade since the first Irish nest of a great spotted woodpecker was found. Dick Coombes celebrates the find in the current edition of Wings, BirdWatch Ireland’s magazine, and Declan Murphy, one