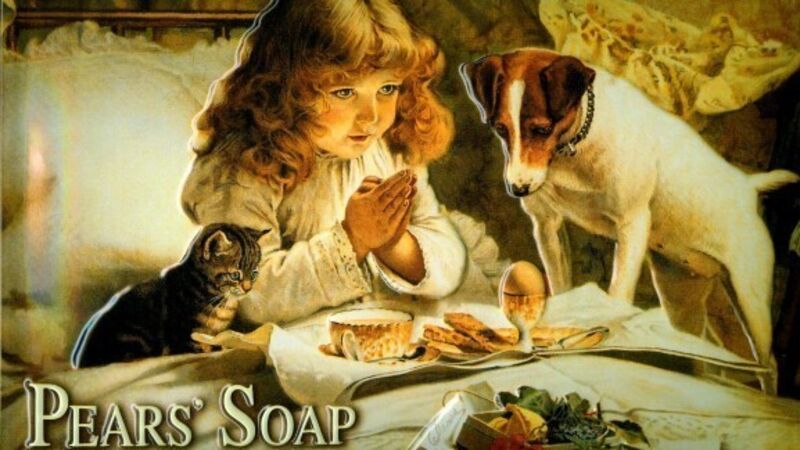

Vintage View: Classic soap advertisements

PEARS’ Soap, that softly withering amber nugget was the first branded clear soap in the world, registered in 1789.

With its comforting antiseptic flavouring of herbs (said by sudsy faced followers to recall the scent of warm biscuits, country gardens, warm laundry or that musk on the top of a smooth dog’s head) the dense gem like transparency is achingly familiar.