Irish Examiner view: Protest uses the power of polite dissent

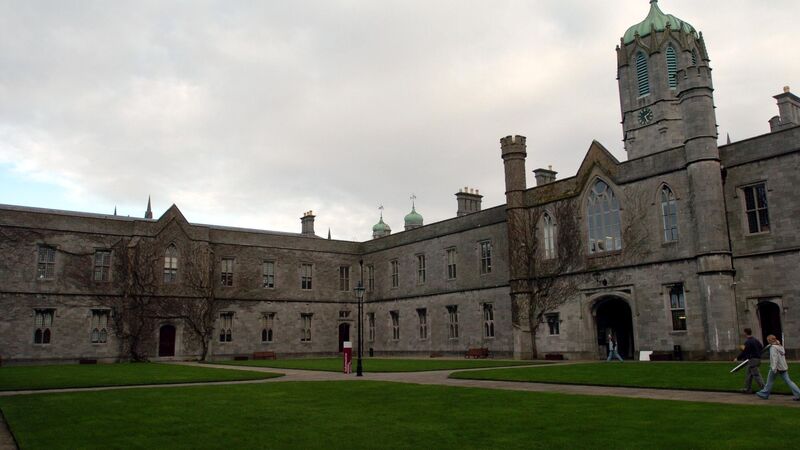

University of Galway's campus. Whether the university will finally sever ties with Technion is unclear. File picture: Ray Ryan

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEThere is a particular sting in the act of protest that doesn’t shout, doesn’t blockade, or disrupt. The kind that simply says “no”.

In recent days, the University of Galway has felt that sting three times over, as actor Olwen Fouéré, filmmaker Margo Harkin, and now American historian Kerby Miller have each refused the institution’s offer of an honorary doctorate. One act of dissent can be dismissed as an anomaly, two, a trend, but three is a reckoning.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Thursday, February 12, 2026 - 10:00 PM

Thursday, February 12, 2026 - 10:00 PM

Thursday, February 12, 2026 - 9:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited