Irish Examiner view: John Bruton was a formidable servant of the Irish nation and of peace

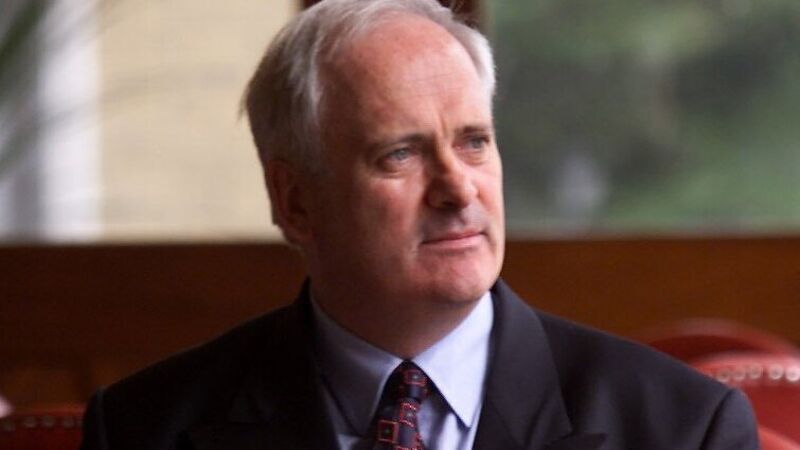

In the course of his career, John Bruton saw at first hand the swings and arrows of political fortune. Picture: Kieran Clancy/Irish Examiner Archive

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBEIn his Dáil speech congratulating Bertie Ahern on becoming taoiseach in 1997, John Bruton pointed to the economic boom which the new government would inherit from his administration.

Bruton, who died on Tuesday at the age of 76, would have been forgiven a few regrets that he would not remain as taoiseach when the Celtic Tiger began to roar at the turn of the century.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 1:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 12:00 PM

Monday, February 9, 2026 - 6:00 AM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited