Rosita Sweetman: Dublin ‘hidey hole’ love story cut short

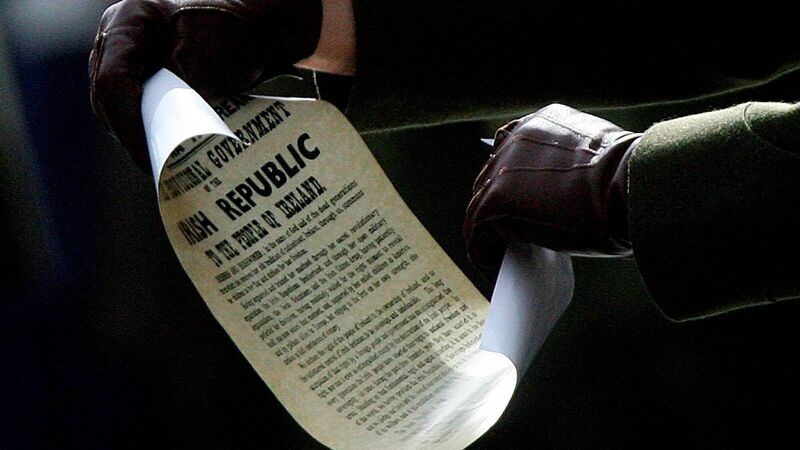

Winifred set about turning Seabank into a depot for the making and distribution of first aid supplies for the IRA fighters in need of refuge. One such fighter was deputy chief of staff Austin Stack. File Picture: Niall Carson/PA