TP O'Mahony: Sixty years on, Vatican II's business is still unfinished

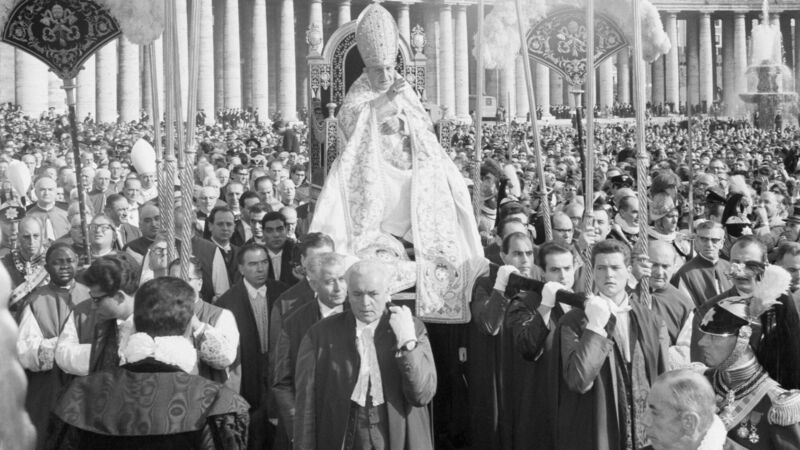

From the moment Pope John XXIII announced the Second Vatican Council on January 25, 1959, speculation about its aims, objectives and outcome intensified.

The 1960s gave us the Beatles, lunar landings, JFK in the White House, the Pill, Women’s Lib, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, the Cuban missile crisis, the death of Marilyn Monroe — and Vatican II.

The latter — properly known as the Second Vatican Council — formally ended on this day 60 years ago after the last of its 16 documents — the Declaration on Religious Liberty — was promulgated by Pope Paul VI.