TP O'Mahony: Whatever its aberrations, Catholicism kept society together

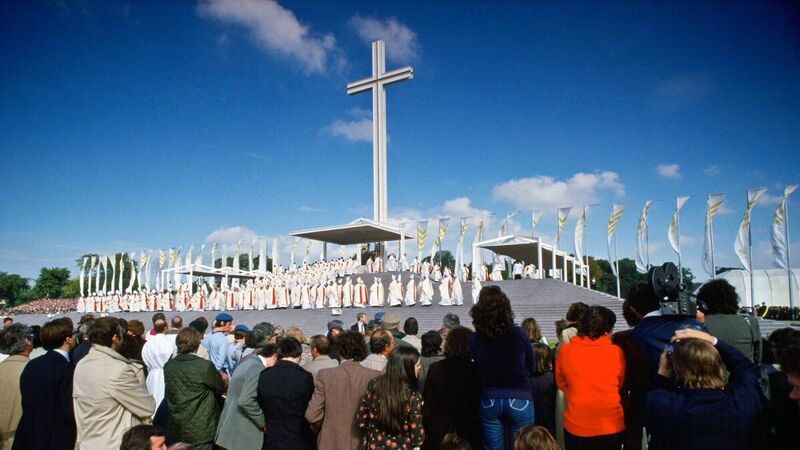

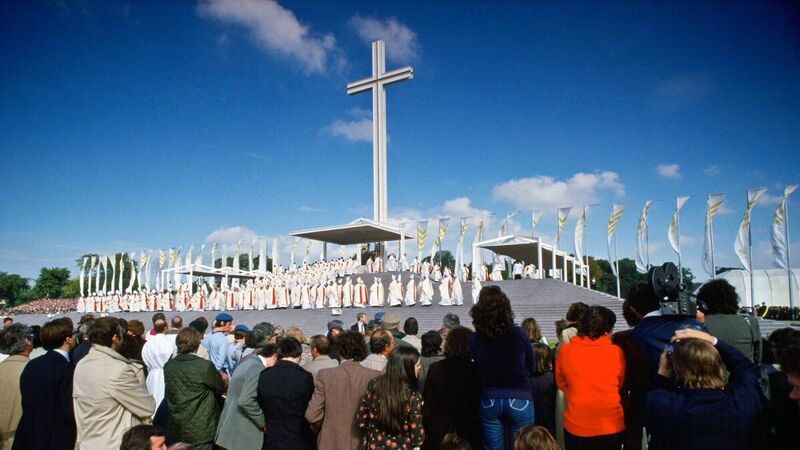

Knock, 1979: Pope John Paul II's visit to Ireland was a very different event than it would be today. Picture: Tim Graham/Getty Images

Try from €1.50 / week

SUBSCRIBE

Knock, 1979: Pope John Paul II's visit to Ireland was a very different event than it would be today. Picture: Tim Graham/Getty Images

STANDS Ireland where it did? The Shakespearean idiom is borrowed from Macbeth, with Macduff’s question (about Scotland in the play) eliciting this response from Ross, his fellow knight: “Alas, poor country, almost afraid to know thyself.”

Is this where we’re at? Who are we now? In the Ireland of the 1950s, when I was growing up, these questions were much easier to answer. It was an Ireland at the centre of which stood three great institutions: The Catholic Church, the Gaelic Athletic Association, and the Irish Press.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Newsletter

Keep up with stories of the day with our lunchtime news wrap and important breaking news alerts.

Newsletter

Sign up to the best reads of the week from irishexaminer.com selected just for you.

Saturday, February 7, 2026 - 9:00 PM

Saturday, February 7, 2026 - 9:00 PM

Saturday, February 7, 2026 - 11:00 PM

© Examiner Echo Group Limited