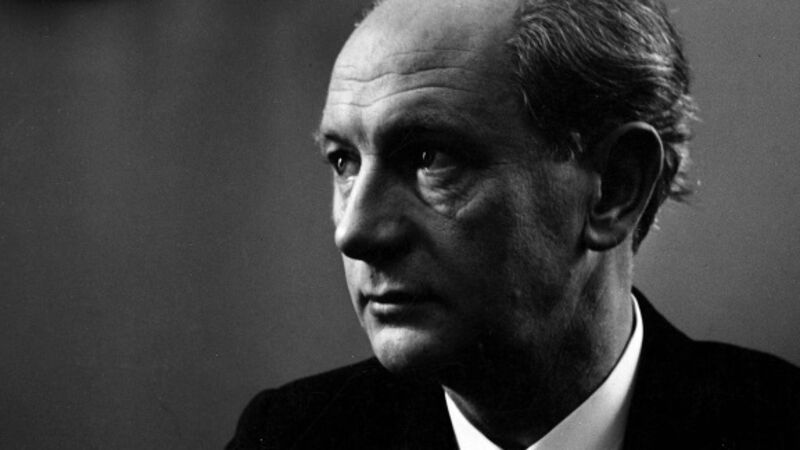

Jack Lynch: The reluctant Taoiseach

THE first indication that Seán Lemass was about to step down as Taoiseach was when Minister for Industry & Commerce George Colley cut short a trip to the United States and returned home unexpectedly on October 31, 1966.

His refusal to be drawn on the reasons for his return, fueled the speculation that the Taoiseach was stepping down. Three other ministers were also out of the country. It was believed that Lemass was waiting for their return before making his formal announcement.