Tunisia terrorist cell promises more attacks in video

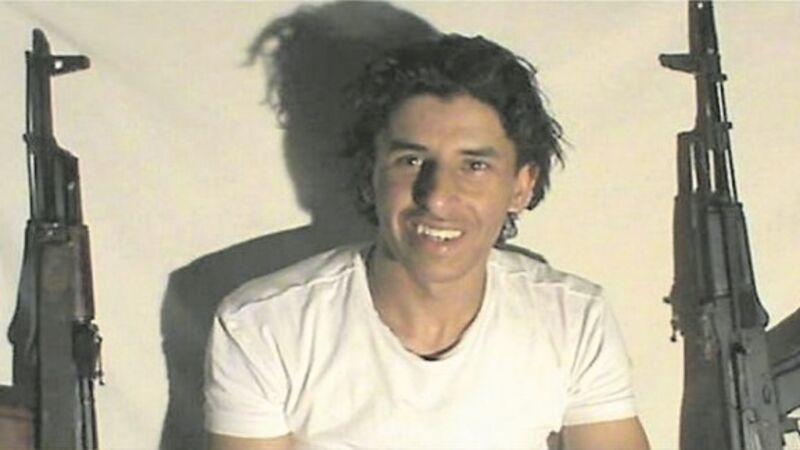

Port El Kantaoui, the tourist complex 10km to the north of Sousse where 23-year-old Seifeddine Rezgui gunned down 39 tourists, is deserted.

On the outskirts, a novelty train crawls along the roadside; empty but for two perplexed-looking middle-aged tourists. On the pristine white sands of the beach where Rezgui had rampaged, the remaining tourists make their way to the site of the massacre, carrying flowers and makeshift signs of hope and consolation.