Sat, 31 Aug, 2013 - 01:00

Stephen Rogers

“You don’t get me, I’m part of the union”

The Strawbs song has rung out across trade union conferences for 40 years, both here and in Britain.

Already a subscriber? Sign in

You have reached your article limit.

Subscribe to access all of the Irish Examiner.

Annual €130 €80

Best value

Monthly €12€6 / month

Introductory offers for new customers. Annual billed once for first year. Renews at €130. Monthly initial discount (first 3 months) billed monthly, then €12 a month. Ts&Cs apply.

CONNECT WITH US TODAY

Be the first to know the latest news and updates

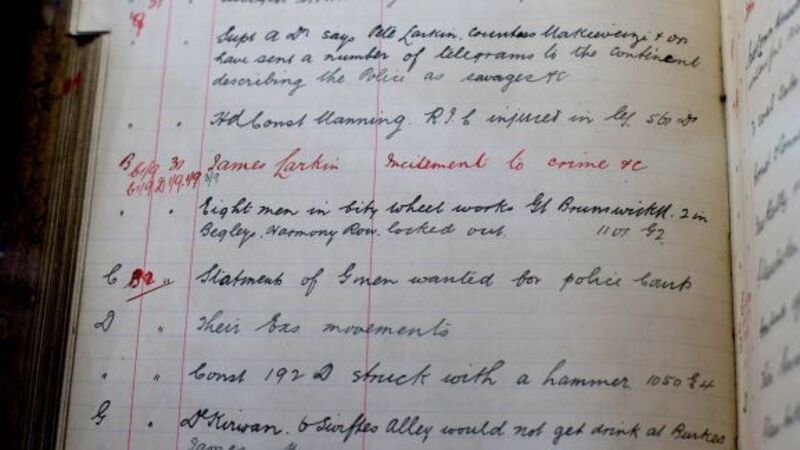

CourtsAnalysisPlace: BritainPlace: O’Connell StPlace: IrelandPerson: Stephen RogersPerson: William Martin MurphyPerson: James LarkinPerson: Francis DevinePerson: DevineEvent: Dublin 1913 LockoutEvent: Irish Congress of Trade Unions biennialOrganisation: StrawbsOrganisation: Dublin Tramway CompanyOrganisation: ITGWUOrganisation: SIPTUOrganisation: Labour PartyOrganisation: Croke Park II