Clodagh Finn: Anna Frances Levins — ‘The most travelled Irishwoman in the world’

Anna Frances Levins (1876-1941), photographer, publisher, artist, writer and political activist.

I’m getting in early to highlight a significant date on the horizon: March 21 marks the 150th anniversary of the birth of Anna Frances Levins, the photographer, publisher, writer, painter and activist who was once described as “the most travelled Irishwoman in the world”.

She was, in fact, Irish-American but she travelled extensively around Ireland in the early 1900s, photographing and painting a country and a people that she spent much of her life celebrating.

She photographed Patrick Pearse, Éamon de Valera and his personal secretary Kathleen O’Connell, tenor John McCormack and John Redmond to mention a few high-profile Irish subjects.

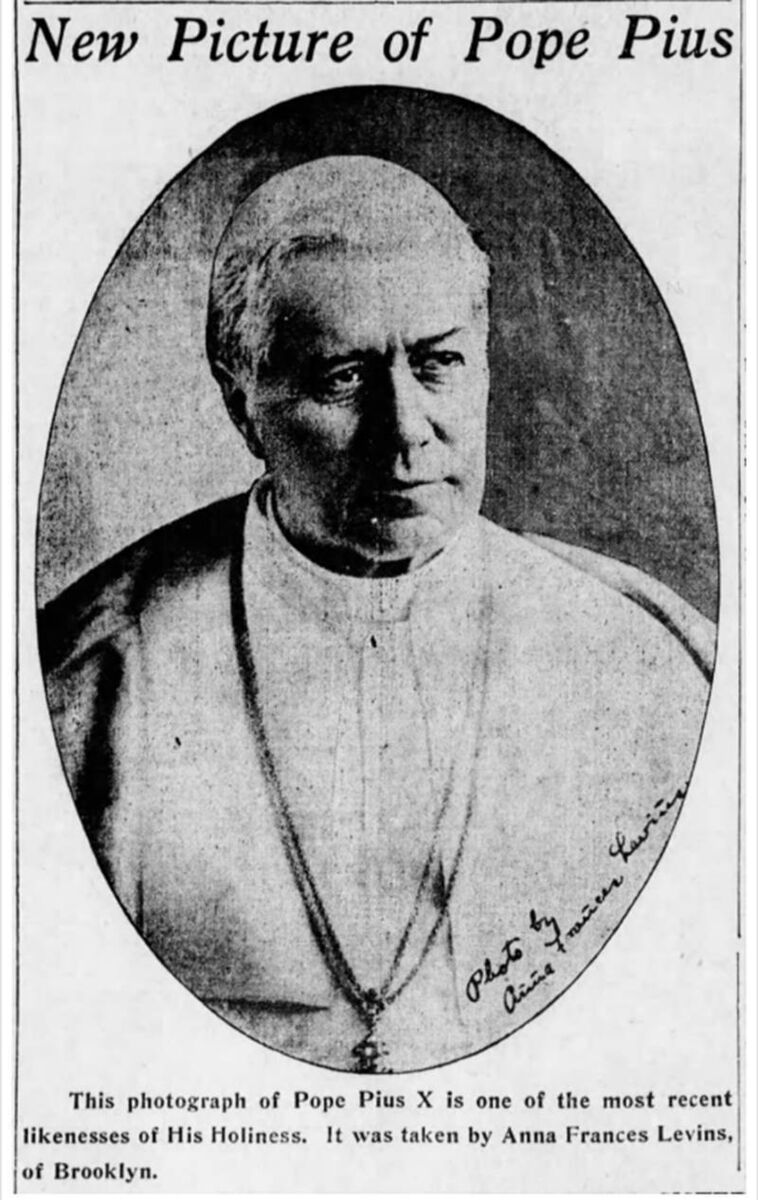

But her scope was wider and more international. To pick two people who could not have been more different, she did thoughtful portraits of Pope Pius X and Elisabeth Marbury, a pioneering literary and theatrical agent who, from 1892, was living openly in a same-sex relationship with the famous interior decorator Elsie de Wolfe.

HISTORY HUB

If you are interested in this article then no doubt you will enjoy exploring the various history collections and content in our history hub. Check it out HERE and happy reading

Levins painted too and these words from the Kildare-born poet and nationalist Teresa Brayton allow us to squint through the keyhole of her New York studio in December 1921.

Brayton wrote: “One evening last week I called in for a few minutes’ chat and a little rest at the beautiful studios of Miss Anna Frances Levins... I had seen her great picture of the heroic young martyr, Kevin Barry, which created such a sensation when on exhibition in the Irish Industries Depot on Lexington Avenue, and so was anxious to get a glimpse of her late study of Michael Collins, head of the Irish Republican Army, whose daring exploits have made him the idol of half the world.

“By great good luck I found the picture had just been finished and set up on a great easel in the large gallery, an immense tricolour Green, White and Orange flag draped gracefully above it. Surely it is a great picture! That clean-cut face with its flashing grey eyes seems to be so much alive one almost expects to see the fine lips part in either a challenge or salutation.”

She went on to describe Levins’ painting of Cú Chulainn who was depicted against a dramatic stormy sky; a heroic representation of Ireland’s glorious, mythologised past.

Teresa Brayton’s comments, printed in the , are fascinating for many reasons, not least because they give us an insight into how these two creative Irish-American women were at once shattering stereotypes and creating them.

Anna Frances Levins made no bones about the latter. She presented an idealised view of Ireland and made no apology for it, calling the place where her parents Peter and Nancy ‘Nanno’ Hale Levins were born, her “Sireland”.

She even considered all that Ireland had to offer — its culture, its people, its industries — superior to anything on offer in America and, in the early years of the 20th century, campaigned hard for Irish independence.

While she painted the country’s heroes and photographed its revolutionaries, politicians and artists, she also invited ordinary Irish immigrants, both Catholic and Protestant, to visit her studio.

She burned turf in the grate and wore Irish linen to make them feel at home. Her aim? To challenge the ingrained prejudices often faced by Irish immigrants when they first arrived at Ellis Island.

Anna Frances Levins’ own life did much to challenge ingrained ideas too. Her photographs, which ran in the prestigious likes of the and , might have cast her as “the Irish American image maker” but she was also a woman who cast off the conventional image of what it was to be the daughter of Irish immigrants in the US.

She was born on March 21 in 1876 to Louth natives Peter Levins, a builder from Drogheda, and his wife Nancy ‘Nanno’ Hale Levins, a couple with means who lived in Manhattan and later in a large house in the Bronx.

Their young daughter had opportunities and early mentors who encouraged her. While at school, her instinct for art was encouraged by two of her teachers, a nun and priest. In her early 20s, she was apprenticed to the eminent New York photographer George Rockwood who, in turn, noticed that she had a singular talent for portraiture.

He saw her photograph of an American Civil War veteran and recognised that she had a gift for capturing the essence of a personality. Anna Frances Levins somehow managed to capture the soul in the image, as independent researcher Eve Kahn describes it.

Kahn, a former antiques columnist, stumbled across Levins while researching Thomas C Levins, an uncle, and happily tripped down a rabbit hole unearthing a treasure trove of material that offers us new insights into this overlooked woman.

In her own lifetime, Levins was lauded as a pioneer, “a genius woman” and a leader in Irish cultural circles.

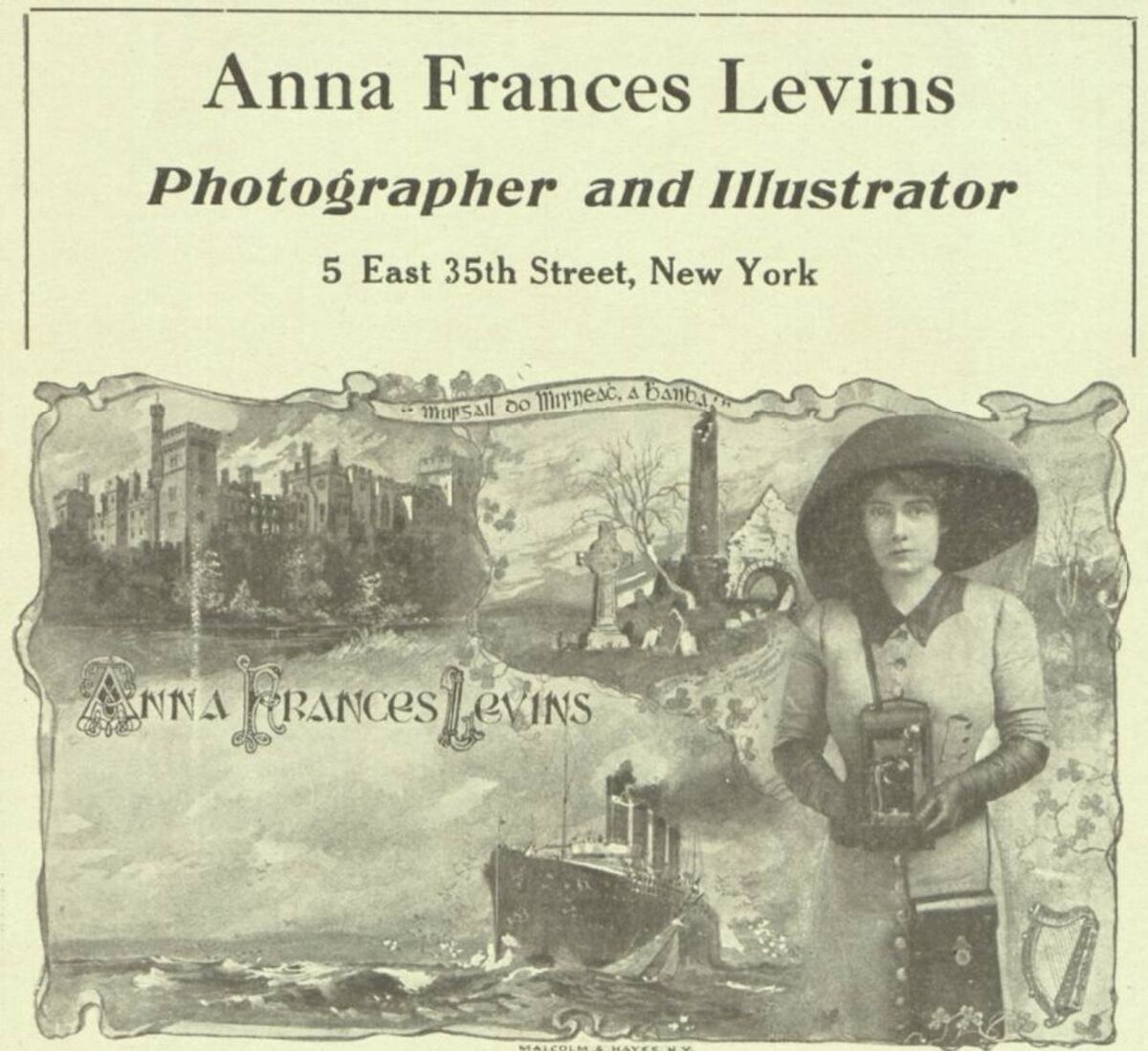

By 1909, she had established her own studio in Manhattan, at 5 East 35th St, and her comings and goings were reported in the press. “Miss Levins to go abroad,” ran a headline in the in August 1909 over an article informing readers that “the distinguished Irish-American portraitist” was on her way to London to exhibit her work.

Miss Levins, it added, “was one of the few women to have real success in photography in all its phases”.

That success must have played a role in prompting the American Irish Historical Society (AIHS) to appoint her official photographer in 1911. Even so, that was a bold step. She was the Society’s first female photographer and the only female board member for a number of years afterwards.

Kahn found references describing Levins as “this woman genius in our midst” who was praised for bringing in more female members.

Meanwhile, she travelled widely all over Ireland and into its remotest parts. She went to Newfoundland — she said it reminded her of Ireland — and gave lectures on a circuit so wide that the dubbed her “the most travelled Irishwoman in the world” in 1914.

Anna Frances Levins also ventured into publishing and founded the , of New York and Dublin, which again focused heavily on Irish literature, history and culture.

Her marriage to Thomas Henry Grattan Esmonde, an Irish baronet, in 1924 marked the end of her independent professional life, but the start of a new one.

She closed her studio and moved to Ireland, dividing her time between Grattan House in Dublin, and Wexford. The couple travelled widely too and, it seems, Levins grew into her role as Lady Grattan Esmonde.

Eve Kahn found letters in Rome describing her as a “hoity-toity woman with an American accent”, a stark contrast to earlier letters written to priest friends in America where her self-doubt was laid bare.

As Kahn points out, her brochures were bold and confident but her private letters revealed a woman who was very self-deprecating, but perhaps that is the story of working women the world over.

Here we are at the end, having just barely grazed the surface of this accomplished woman’s life, but there is still space to suggest that the many ministers travelling to the US for St Patrick’s Day might take a moment to recall her life and work.

There’s a link to the saint too, if one is needed. Anna Frances Levins was married in St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York and, two decades later, her funeral took place there when she died on July 15, 1941.

I prefer to remember when it all began — 150 years ago next month.